April 26, 2011

There is something that's been on my mind recently, and it's what I'll call the Acquired Needs of Software Engineers. Keep in mind this is a very young concept in my own brain, yet to reach maturity and certainly still vulnerable at this point to drastic changes in my opinion. It's really just an inkling, but one that's been nagging at me. Who knows? Maybe by writing about it, however briefly and incoherently, I'll improve my own understanding of what it is I'm talking about.

So, to understand what I mean by acquired need, consider a caveman.

What does this guy need? Not a whole lot, right? I mean, the essentials, sure: food, water, shelter... anything else? Not really. A caveman needs basically those three things, and that's it.

Now consider a "modern" man.

What does this guy need? Or let me rephrase that: what would he say he needs? Probably something like...

- His mobile phone

- His computer

- His car

- His business clothes

- His gym membership

- His GQ subscription

- etc.

OK, maybe not all that stuff exactly; but you get what I'm saying. Those things—at least some of them—feel like needs nowadays. Certainly, smart phones (for those of us fortunate/unfortunate enough to have them) and mobile internet access are feeling more and more that way (internet access is already considered a human right by some nations).

But they're not really needs, are they? In fact, before these things were invented, we never missed them. And that's why I refer to them as acquired needs.

(Note: Apparently there is an actual Theory of Acquired Needs developed by a guy named McClelland; I am not referring to that theory. When I use the term, I am really not utilizing any formalized concept—just a notion of mine, which I hope is reasonably clear to those reading.)

Now, there's nothing wrong with cars, or the internet, or smart phones; those are perfectly good things, if you ask me. But what's not good about these things, I would argue—and I think I know of a certain someone who would agree with me—is that we have reached a point where we feel we cannot function without them.

Let's face it: a need is, among other things, a vulnerability. If you need your smart phone to function normally, what happens when your smart phone stops working? Or you lose it? You basically stop functioning for however long it takes to resolve that issue. Multiply that by the number of acquired needs you have. Do you need the internet? What do you do when your ISP is temporarily down?

In my relatively short time spent on this project, I've started to observe something disturbingly similar going on in the world of software. This has been an eye-opening experience for me because my last job was at a company where we had very little in the way of what most professional developers would call "process"; we basically followed this daily routine:

- In the morning, we'd discuss some new feature or idea for an algorithm (I worked for a trading firm).

- We'd start coding like crazy...

- without writing many (or any) tests

- without checking in code to a build server

- without any sort of code reviews

- without any QA environment

- Possibly later in the day, or the next day (if the coding effort was extensive), we'd deploy... to production.

If you're a self-respecting professional software engineer, like many of my teammates, you may have just felt your jaw hit the floor. Yes, that's correct; we would typically go from inception (discussing a new idea in the morning) to a production deployment in under 24 hours.

You must have had a lot of bugs!

We definitely had bugs. "A lot" is tough to define. I would bet money they were fewer than most experienced software professionals would predict.

Your code must have been a huge mess!

Absolutely. Moving on.

What was your performance like?

Honestly? Quite fast. A huge portion of the time spent writing "good" software involves developing abstractions to reduce code size, improve code flexibility/maintainability, etc. Abstractions aren't free. When your code uses public fields instead of properties (in .NET), switch statements instead of polymorphism, arrays instead of more sophisticated data structures, and so on and so forth... OK, I won't keep going, lest readers start thinking I'm a crappy developer. This is actually a topic for a whole other blog post.

I'm actually not trying to say that my old job was great because we were so light on process. To the contrary, we definitely accumulated some serious technical debt. But that is also a topic for a different blog post. I'm only trying to convey the fact that coming from my previous job, I was not used to having lots of external dependencies that I was required to lean on in order to do my job.

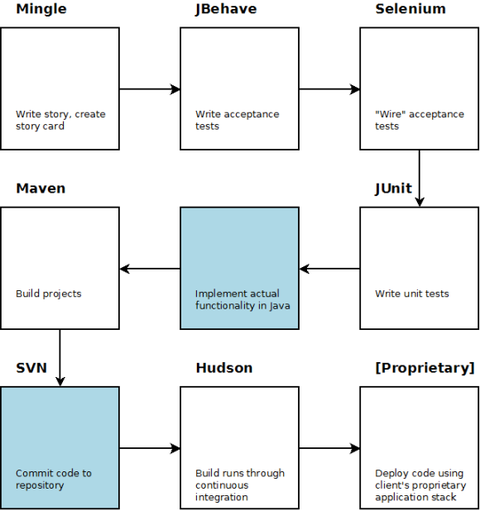

Fast forward to now. Below is a crude diagram depicting the process followed by my current team for developing new functionality.

Highlighted in blue are the only two steps we also followed at my previous job.

To be clear: I can't really object to any of the components in the above diagram. Mingle is actually a really cool piece of software, in my opinion (full disclosure: it happens to be developed by ThoughtWorks Studios). I'm fairly new to BDD and acceptance testing frameworks (in .NET I only dabbled briefly in SpecFlow); but I can definitely see the appeal of JBehave. For automating browser-based tests, Selenium (actually, we use the newer WebDriver) is an undeniably powerful tool. I could say basically the same thing for every tool in the diagram above (though I'd personally prefer a distributed version control system like Mercurial to SVN).

But here's the thing: when we require each and every one of the above tools just to deliver a piece of functionality, sometimes I wonder whether we have too many acquired needs. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, right? Suppose our build server (Hudson) goes down. Or our Maven dependencies get screwed up for some reason. Or our acceptance tests fail because of some quirk in JBehave or Selenium (and notably not due to an actual bug in our code). These things all cost us time and effort, and therefore they cost the client money.

There's this assumption that overall, the pros outweigh the cons. What these tools cost, they more than make up for in terms of increased software quality, greater confidence, higher productivity, and so forth. I'm just not so sure. Because I think back on my last job, where we used none of this stuff; and sometimes I think, "We could have developed features X, Y, and Z faster over there"—at a level of quality that wouldn't have been noticeably different from the user's perspective.

It bears repeating that, as I stated up front, this is just something that's been on my mind; it is not a full-fledged opinion I harbor about the right way to build software. I'm still kind of working on forming that opinion. For now, though, it's just something I find myself questioning, perhaps a bit more than those around me.

I think this really started to materialize fully in my brain when I was talking with a particularly bright coworker last week. He was lamenting how little we've achieved on this project relative to what he expected when it first started (he'd been on the project since its inception); and at one point he made a very honest statement:

Maybe I'm just too spoiled to be productive in this environment. It's like I've forgotten how to code when I'm not part of a well-oiled machine.

I'm paraphrasing; and my coworker wasn't actually referring to our tools (the diagram above) but in fact to the miles of red tape that exist within the client organization, and to the lack of say we've been given over the technology choices for this project. But what struck me was the very notion that he, a stellar developer, could be "too spoiled" to operate under certain circumstances—basically, that he had acquired so many needs, he was nearly crippled when they weren't all met.

So I find myself questioning whether it's wise for me to wholeheartedly embrace all these tools, these processes, these external things, lest they become acquired needs to me too. I'd like to believe that if the opportunity arose for me to work on some really exciting new software, but environmental constraints prevented me from having access to things like a project management tool or a CI server or heck, even a unit testing framework, I could still write software.

I'm reminded of a video my brother and I watched once of the great drummer Terry Bozzio, known for both his incredible talent and his insanely large drumkit.

In the video, Bozzio said something along the lines of "I can't even play on a regular kit anymore." I remember my brother shaking his head and making a comment like "If he can't play on a standard 5-piece kit, is he actually even good?"

A preposterous question, no doubt—particularly to any Bozzio fans who might be reading this (anyone?)—but maybe still a question worth asking.