March 16, 2011

Earlier today a user on Stack Overflow posted the question, "Does the ?? operator short circuit?"

A fair number of users responded with the obvious jab: "Why don't you just write a test and see for yourself?" It's a pretty reasonable question. To find the answer one way or another would only require a few lines of code in a simple tool (like SimpleDevelop!) and less than a minute.

But the user replied, "I wanted to know authoritatively."

Now that is a tricky notion. And it actually relates to one of the strongest arguments for TDD (test-driven development) and CI (continuous integration) out there.

Here's the million-dollar question: how do you know something authoritatively (in software1)? How can you ever be sure that something works?

The accepted answer to the Stack Overflow question cited the C# spec, providing a concrete, documented answer. And this certainly seems like the "final" say, especially with documentation as "official" as the MSDN documentation for .NET.

The user who posted the answer had this to say:

If you only try it, you can never be sure if the behavior you observe is (a) something you can always rely on or (b) just some implementation detail of the compiler (e.g. some optimization). To be on the safe side, you need to check the documentation for the specified behavior.

Now, before I go any further, I just want to be clear: I basically agree with this, and I don't intend to in any way imply that it's wrong—only that it is just one way of looking at things.

Here's another: maybe documentation doesn't give us the final say either. After all, those of us who've been in the software industry for more than a week know that specified behavior and actual behavior are (sadly) seldom the same thing.

This can happen for multiple reasons. One reason is that the specified behavior wasn't properly thought out, or doesn't meet the targeted business need(s) as well as the software itself does. This is actually a fairly OK scenario: "The software's right; we just goofed on the documentation."

Another possibility is that the specified behavior is correct, but the software doesn't properly match it. There could be a bug, or something more subtle—perhaps the treatment of a special edge case that would rarely occur in a real environment (Turkish-I problem, anyone?).

A third possibility, naturally, is that both are wrong: the spec isn't right, and neither is the code.

But even supposing they are the same thing, software changes—often more frequently than documentation. Which means that documentation can actually be correct one day and incorrect the next. (I'm not saying this is the way it should be, of course! In an ideal world, yes, documentation would always match actual behavior. But we're talking about knowing things for sure here.)

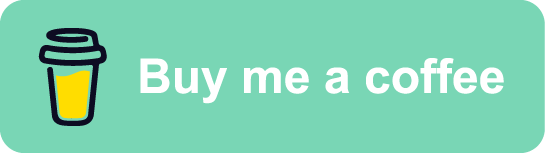

And then there's always this.

Quite often, software just flat-out isn't documented at all.

But we aren't talking about just any old documentation! This is a language specification!

Yes, yes, of course. But what is a specification, really, if not simply documentation that has been deliberated upon very carefully? (Also, there can even be flaws in programming languages with specifications! These things are written by humans; what can you do?)

What I'm getting at here is that there's a better way to be sure that something works the way you expect it to: not to just "try and see" (and assume things will always be that way), and not just to read documentation, either. This is what continuous integration is really about: constantly testing code to verify that it works as expected.

What you do is this: you figure out what your expectations are, and you write some tests to check code against these expectations. Then you write the code to actually pass the tests. That's TDD. From there, whenever you make changes to the code and commit them to SCM, a CI server runs the tests to ensure that the code still works as expected. Now you aren't relying on a fragile "Well, it worked when I tried it last week" measuring stick, nor are you making any assumptions about the correctness of documentation. You're truly verifying that the software works the way you expect, in a way that provides greater certainty than any other method.

To close, I'll use an analogy that should hopefully solidify this idea. Suppose there are two bridges leading across a large chasm. From merely looking at them, it is difficult to judge how solid or well-constructed either one is. But one is crossed by other travelers throughout the day, every day, and has been since its construction. The other has not been crossed in years, though there is a sign posted which says, "This bridge was built to last for 50 years without needing maintenance."

Which bridge would you choose to cross? Really it should just come down to this: which evidence carries more weight, words on a sign, or the continuous testing of countless travelers over time?

Personally, I have trouble seeing how you could argue against the latter.

-

In general, that question is far too "big" for me to answer. ↩