February 09, 2021

About a year ago, a colleague reached out to me for some advice. He was a peer of mine and was receiving feedback from his manager that he wasn't meeting expectations. He suspected that I was faring a bit better within the organization and wanted my opinion on how he could improve.

Something this colleague said struck me, and it made me a little sad. He said, "I've always thought that my work would speak for itself."

Back when I first interviewed to join the Bitbucket team—over six years ago (!) now—I met with the GM of the Dev Tools1 division. He talked about the very special culture Atlassian has, and I'll never forget the way he described it. He called it a company full of "humble overachievers". It sounded lovely, the notion of working with people who are super-smart and highly motivated yet humble and down to earth.

Two or three years later, one of Atlassian's founders visited the office in Austin, Texas and sat down for a fireside chat with the local team. One of the questions he answered was "What is Atlassian's greatest weakness?" I won't share his specific answer to the question, but I will share the preface he gave, because it resonated with me. He noted that often our greatest strength and our greatest weakness are one and the same. Sometimes the very thing that makes you special and sets you apart can also be what holds you back.

I don't remember everything I said to my colleague, but I remember telling him this: your work does not speak for itself. At least not in a large organization. You need to speak for your work, because there's too much going on, and if you don't make people aware of the value you're providing then they aren't going to magically notice.

The radius of influence

Here's where I think the idea of work-speaking-for-itself comes from. Given a small enough group, it works. Without calling any attention to themselves, people can stand out in small groups simply by demonstrating their talents. This is because of the radius of influence: people naturally pay attention to those in their immediate environment.

Imagine a primary school classroom with 30 students. Everyone is given the same assignments, takes the same tests, and is graded on the same scale. In this environment, if you are legitimately the most gifted student, you can afford to be as humble as you like; people will still notice you because you'll stand out based on merit alone. You and your classmates are all performing the same tasks, and you're doing the best job. Unless you're actively trying to hide that fact, others will find out one way or another.

Some students will notice your consistently good scores as the teacher hands back your graded assignments. Some will notice that you always answer correctly when the teacher calls on you. Some will notice that you always seem to complete the exam before everyone else. Still others may notice none of these things but will still hear your name mentioned in conversation. Everyone is either within your radius or connected to it through someone else.

Now think of a street performer, someone who shows off their talents to passersby for tips. In some ways this is not so different from the classroom: people still notice the street performer as they walk by, similar to how students might notice their most gifted classmates. But for a street performer, the goal is to make a powerful impression in a very short period. Only a small percentage of pedestrians will stop and watch you, and only a percentage of those will bother to pay you for your performance. People are entering and leaving your radius so briefly that, first, you must be quite good, and second, you must perform in a location where you'll be exposed to many, many people.

The scalability of pull-based information distribution

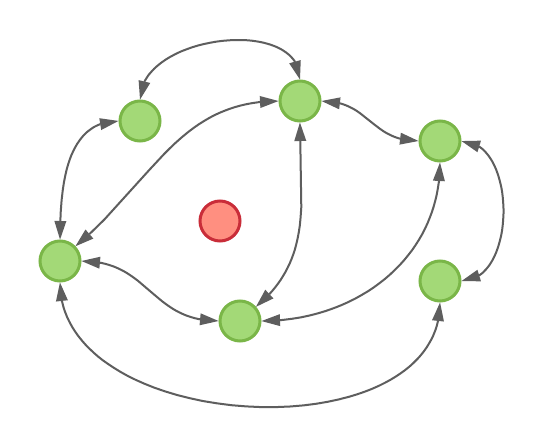

Consider a system with N nodes. Every node produces information that must be propagated to other nodes. Bottlenecks in the flow of information can cause individual nodes or small clusters of nodes to become overloaded, which is doubly harmful as it not only inhibits these nodes from contributing to the system, it also inhibits the nodes from receiving information from other nodes. The net effect is information blockage which jeopardizes the health of the overall system.

I've just described most organizations. True dysfunction occurs when information is isolated within individuals or teams. It can reduce efficiency as work is duplicated; but even worse, it increases the risk that different teams pursue contradictory or mutually exclusive projects. For example, one team might attempt to integrate with another team's component or service, even while the other team is actively discussing deprecating it.

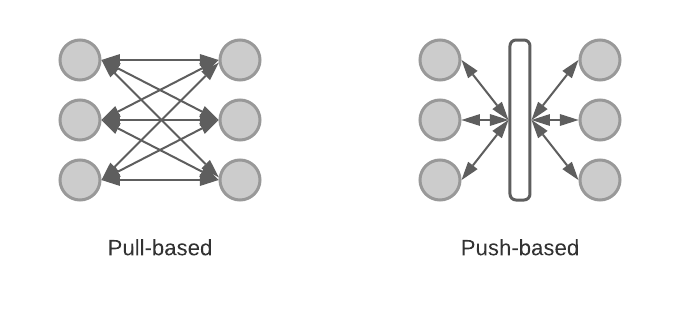

One implementation of sharing information between nodes would be a pull-based system: on some interval, every node polls every other node for new information. This works perfectly well in small groups. A daily standup meeting, for example, is essentially this: every member of a team, typically fewer than 10 individuals in my experience, is polled for an update every day. This allows for everyone within the group to be informed of everyone else's status generally within 24 hours.

But consider the algorithmic complexity of this implementation. It is O(N2): every node must poll every other node. For sufficiently high values of N, this is simply not tenable. Just imagine if a corporation like Apple, with over 100,000 employees, attempted a company-wide standup meeting!

A better implementation for information sharing at a larger scale is a push-based system. Nodes broadcast when they have new information via some centralized channel, and other nodes can subscribe to this channel. For information that is particularly important or impactful, these subscriber nodes can then broadcast to additional channels.

This system is imperfect as it does not ensure that all information is propagated to all nodes, but it is reasonably good at getting the most relevant information distributed while avoiding total information siloing. More importantly, it is viable in a way that a pull-based system—picture that Apple-wide daily standup meeting—simply isn't.

The luxury of modesty

In case the previous two sections seemed unrelated, allow me to connect the dots. You can get away with a pull-based system for distributing information as long as:

- You don't work with too many people (small enough values of N); and

- Everyone you work with, everyone who needs to know what you're doing, is within your radius of influence

This may be true at a small startup, but it's less true the larger your organization becomes. Eventually you must forgo modesty and learn to broadcast your contributions; you must participate in the push-based system. Otherwise your work will go unnoticed; or worse, the work you're doing will end up being counterproductive.

At this point it's worth pausing to consider why we generally think of modesty as a good thing. Why do we want people to be humble?

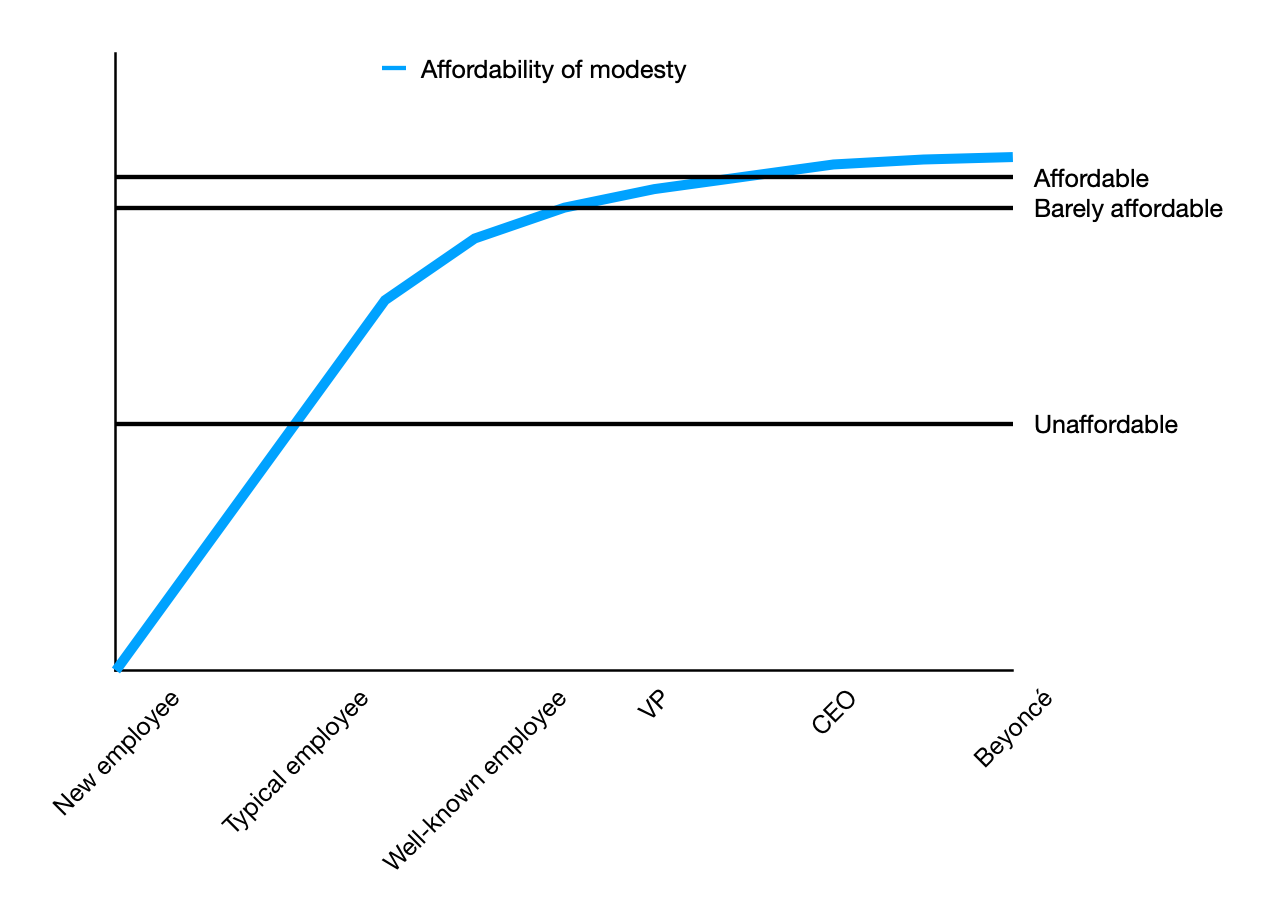

I don't know the answer, but I have a hypothesis. Everything I've said so far is true for most people. The average street performer needs to choose their location wisely to maximize exposure, and the average worker needs to call attention to the work they do. On the other hand, a world-famous celebrity like Beyoncé or Taylor Swift can do very little to promote themselves and still be showered with attention.

One way of thinking about this is that not everyone has the same radius. Some individuals have a radius so big, virtually anything that they do will be noticed on a large scale. These individuals don't need a push-based system, because everybody's pulling. They can afford to be modest.

I believe that modesty is a luxury, and that we don't actually admire people for being modest per se. We admire modesty in those who can afford it because of what it signals: that they have achieved a level of recognition that allows them not to worry about self-promotion. In contrast, if you aren't aware of someone's achievements, you can't even see their modesty; it is only visible to those who know what they've actually done!

Being modest when no one knows of your achievements is like being a street performer on a street with no pedestrians, hoping for tips.

Lessons to learn

Ever since that conversation in which my colleague expressed his desire for his work to speak for itself, I have shared this perspective with many peers, as well as employees who report to me. Those of us mere mortals who aren't blessed (or cursed!) with the constant attention of a massive audience need to be our own cheerleaders. It's what's best for us but also what's necessary for the organizations to which we belong.

This is important for managers to understand. Part of supporting your team is empowering them to speak up—encouraging and prioritizing blog posts, tech talks, presentations, etc. Part of it is also acting as an amplifier, sharing the output of your team with an even wider audience, by every means available: Slack, email, face-to-face conversation2, and the rest. It's not only valuable for your team members' career development; it's critical for your team to be effective within a larger system.

But it's just as crucial for individual contributors to understand this. The signal starts with you. Just as a microphone held in an empty room will capture very little sound, your manager can only do so much to focus attention on your work if you aren't making an effort to share it yourself.

Don't make the mistake of modesty when it's a luxury you can't afford. Don't be a street performer playing on a lonely corner with no audience. Go find a busy intersection and play it loud.