February 04, 2011

Watch the following video and count how many times the players in white pass the basketball. Then scroll down to read the rest of this post.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Did you see the gorilla? OK, the truth is: I did, but only because I was expecting it (the name of the website where I first saw the video, The Invisible Gorilla, kind of gives it away). Apparently a lot of viewers do not see the gorilla, though, because they are too busy focusing on the people throwing and catching the ball to notice it.

It's a fairly well-documented fact at this point that human beings are not so good at multitasking (the fact that that link points to a 2-year-old article right there tells you that this is not news). Rather, we are very quick at context-switching.

Those of you software engineers reading this: does that term sound familiar? I thought so. Context switching is the process of suspending and restoring the state of different threads or processes on a single CPU. More simply, it is akin to shifting one's attention back and forth between multiple things. A good example would be driving while talking on the phone. It's actually impossible to pay attention to both simultaneously, according to neuroscientists; rather, what you are likely able to do when driving while talking is switch between thinking about your driving and thinking about your phone conversation, very rapidly:

Computers are exactly like this too. This is becoming less true now that dual-core, quad-core, even six-core processors (this will likely only keep increasing) have become the norm, at least on desktop computers (and especially on servers, where 24 cores or more is not at all uncommon); but the fact is that a lot of computers out there still have just one CPU, which means they can only do one thing at a time.

Huh? I hear you thinking (yes, I am psychic). What do you mean one thing at a time? I have like 5 windows open at this very moment!

It's context switching! Just like a human who's talking on the phone while driving (which, by the way, is illegal in the state where my wife and I now live), a single-CPU computer running multiple applications simultaneously in, say, Windows (though the OS is irrelevant), is actually just switching back and forth very quickly between programs. It thereby simulates the effect of multiple processes all happening at once.

As I said, this is changing somewhat now with multiple cores. (Wouldn't it be nice if we could have multiple brains, allowing us to truly multitask?) With many computers now capable of executing multiple instructions literally at the same time, a big trend among software engineers designing high-quality software is to study concurrency and its many implications. "Parallelization" has essentially become a buzzword in the industry; and those who have "mastered" it1—like Joe Duffy—are truly revered and respected for their ability to comprehend vastly intricate and complex systems of real-time interactions.

Personally, I've always felt that working on multithreaded code is hard. Like, ridiculously hard. When you consider the fact that our brains are not very effective at multitasking themselves—maybe that's the reason. How can we as human engineers expect to fully consider all the possibilities in any concurrent scenario when we ourselves can't really think of two things at once?

Now back to that invisible gorilla. I had a bit of an "A ha!" moment when thinking about it earlier today. In effect I believe what happens to your mind when watching this video (at least, those of you who didn't notice the gorilla) is analogous to resource locking in a multithreaded software program.

The idea behind locking is this: in order to overcome the absurdly complex challenge of ensuring that every possible combination of simultaneous events has been accounted for—which, given the fact that there is a limit to what sorts of operations a CPU can actually do in one atomic step, is basically impossible—many programming languages provide a mechanism for "locking" a certain resource, allowing only a single thread to access it at a given time. When other threads attempt to access the resource, each one must first wait for the lock to be released. In this way a programmer can safeguard his code against many unpredictable bugs that could result from multithreading issues.

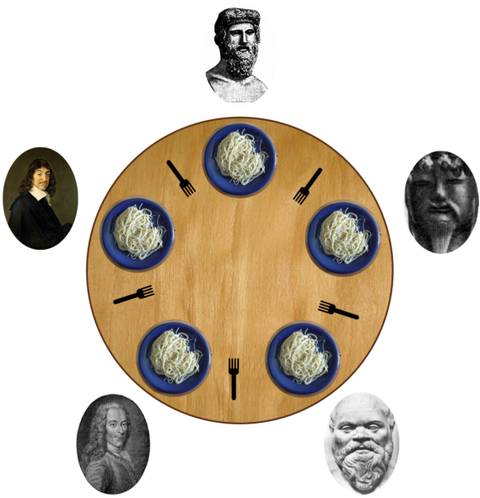

Now, locking poses dangers of its own, namely deadlock. This can happen when multiple threads obtain different locks and each one waits for the other's lock to be released, which will never happen. A well-known illustration of deadlock is known as the Dining Philosophers Problem (sweet name, huh?):

Five philosophers (why five? I have no idea—seems pretty irrelevant) sit around a table, alternating between thinking and eating. Between each pair of philosophers is a fork, for a total of five forks. Each philosopher needs two forks to eat (they're eating spaghetti), but can only use the forks to his left and right.

What can happen is this: suppose each philosopher picks up the fork to his left at the same time as every other. Then each of the five philosophers is holding one fork. Furthermore suppose that they never speak and that each dining philosopher will patiently wait for the fork to his right to be put down without ever growing impatient. This can result in every philosopher being suspended in a state of holding one fork forever!

This type of deadlock is called resource starvation: the philosophers have no more forks, and so they will wait indefinitely. (Note that the presence of even one more fork would solve the above problem.)

In our own minds, I believe that concentrating on a specific process, idea, or event (such as the individuals tossing the ball around) is equivalent to locking our most valuable resource: our consciousness. In doing this we starve our other mental "processes" (e.g., whatever background awareness or perception would have normally noticed a black gorilla walking through our field of vision) of the resource they're waiting on, blocking them out and completely abandoning our usual state of so-called multitasking.

In a sense, it's like we've given one thread high priority and allowed it have the CPU all to itself.

Whether this is a good or bad thing is hard to say. It might in fact just be a matter of opinion. One thing's for sure, though: if concentrating hard on something really is like resource locking in software terms, then I hope we never learn to use both hemispheres of our brains independently.

Just imagine what could happen!

Joe Schmoe, 1975–2011. Loving husband, father of three. Died of deadlock.* *

-

I put the word "mastered" in quotes because, honestly, no one has mastered concurrent programming. The process of understanding multithreaded code has been compared to progressing through the four stages of competence, with the fourth stage being essentially a mythical goal. ↩