January 31, 2021

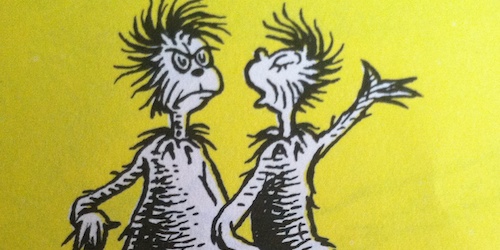

Have you read The Zax, by Dr. Seuss? It's a powerful story. Ultimately it's about the dangers of stubbornness and pride. In the story, the north-going Zax and the south-going Zax both refuse to budge to the left or the right, neither wanting to concede anything to the other side. Each Zax wants the other Zax to be the one to step aside.

What's clear to most readers is that this behavior is counterproductive. The point is driven home by the final pages of the story, in which the world around the Zax moves on: roads and bridges are built around them, progress is made, while they both stand there not moving an inch.

What's also clear to most readers is that both Zax are equally responsible for this stalemate. Each one feels justified in saying, "But if HE would only step to one side, we wouldn't be in this situation." Neither will step up and be the bigger person, putting aside his pride and making way for the other; and as a result they both embody their smallest, pettiest selves.

The story is constructed deliberately by Dr. Seuss to place the two Zax on exactly even footing: neither has anything resembling a moral high ground. There are those who would take issue with this narrative choice as it relates to the story's role as an analogy for real-world disagreements: seldom in the real world do two sides have equally valid views in any objective sense. But this is why the analogy works: in the real world, these kinds of disagreements simply aren't objective. They are subjective, meaning the question of who is right and who is wrong will depend on who's asking and who's answering.

I am a big believer in showing generosity first. When you decide to be the bigger person, often it gives the other side an opportunity to be bigger as well. In my own experience, I have seen this work, and when it does it's almost like a magic trick. But it takes a leap of faith. It often means holstering your weapon while your opponent's gun is pointed at you.

Here's why it works. Tension requires two parties. Consider a tug of war, with both sides pulling the rope taut. The tension in the rope is not a product of either one side; rather, it's the byproduct of the two sides pulling in opposite directions. The only way to alleviate this tension is for both sides to relax. But neither side feels that they can relax, because they can feel the force of the other side pulling. They know that if they stop pulling, but the other side doesn't, they'll lose.

Now imagine that the game of tug of war has gone on for several hours. Both sides are exhausted. Their hands are chafed, their muscles are sore. Everyone wants the game to stop, but still no one wants to lose the game. This shared fear of loss is making everyone continue contributing to an activity that isn't helping anyone.

As a participant in this unfortunate scenario, you may feel that you have no choice. While you want the game to end, you can't afford to stop pulling. And so both sides continue to pull, until one finally lose their strength and get dragged into the mud, leading to humiliation and bitterness and all but ensuring they will lash out at the victors the moment an opportunity presents itself.

Sometimes, thankfully, it doesn't end this way. Sometimes, someone on one side begins to wonder if those on the other side feel the same way they do. They loosen their pull, ever so slightly. Then someone on the other side notices that the tension has lessened, just barely. Suddenly they can afford to give a bit as well. One by one, bit by bit, everyone relaxes. Eventually the rope is slack, and the competition is ended.

But it can only happen if someone decides they're willing to take a risk, because as much as they want to avoid losing, they want to stop fighting even more.