June 22, 2015

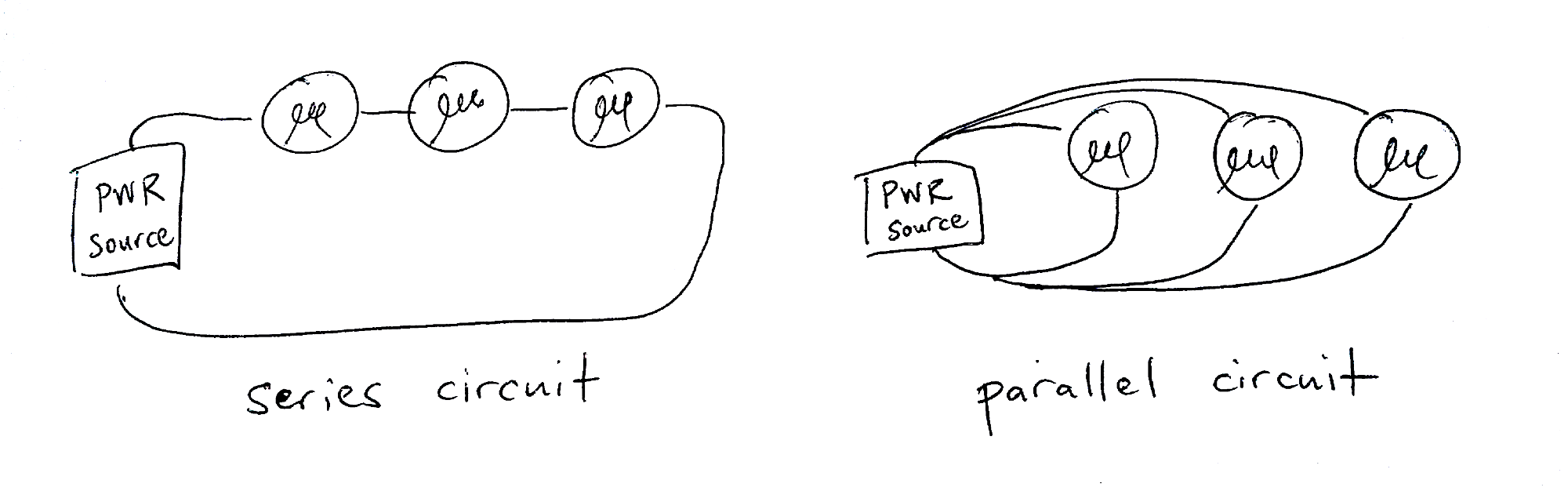

In school, we learned about series and parallel circuits. In a series or "daisy chain" circuit, the same electrical current flows through each component (say, a light bulb) in series, such that a single failed component brings down the whole chain. A parallel circuit, on the other hand, isn't really a single circuit; it's many circuits, all wired up in parallel so that one component can fail without affecting all the others.

Series circuits have at least two serious problems:

- They're fragile: all it takes is one failed component to break everything. Moreover, the bigger the circuit (i.e. the more components it has), the worse this effect is. The odds of any one bulb failing are much greater when you've got 100 bulbs vs. just a few.

- Once they do break, they're difficult to fix. I've heard harrowing tales1 of my parents' generation dealing with strings of Christmas lights that went out, having to check potentially hundreds of bulbs one by one in order to find the culprit.

So series circuits are fragile, and when they do inevitably break, they're tough to fix.

We've all experienced the frustration of not being able to do our job because someone else hasn't done their job. A software developer might like to implement a feature, but she can't because the product owner hasn't spec'd it out, or the design is up in the air. A salesperson might have established relationships with some great potential clients, but the product team has fallen behind on delivering the thing he's supposed to be selling. And so on.

We have dependencies on other people. When those dependencies break down, it prevents us from doing our jobs effectively. Hence, organizations are like series circuits: when one bulb burns out, the other bulbs can't produce light.

A big part of the problem is that we've been trained to internalize a very narrow definition of my job versus someone else's job.

This can be a good thing when everything's functioning properly. By concentrating on just my job and letting other people worry about theirs, I can stay focused and avoid lots of potential distractions.

You know what else works great when every single piece is working? Series circuits.

Where things go awry is when something in the chain breaks, and our narrow focus leads us to say things like "That's not my job."

When things break down, saying "That's not my job" is basically saying, "I'm okay with this circuit being broken." In an organization full of smart, competent, motivated people who do their jobs well, all it takes is one person who doesn't do their job well to neutralize an entire project, or at least a significant chunk of it. When that person fails (or refuses) to do his job, the people depending on his work can't do theirs. As a result, those further down the line can't do their jobs either. And on and on.

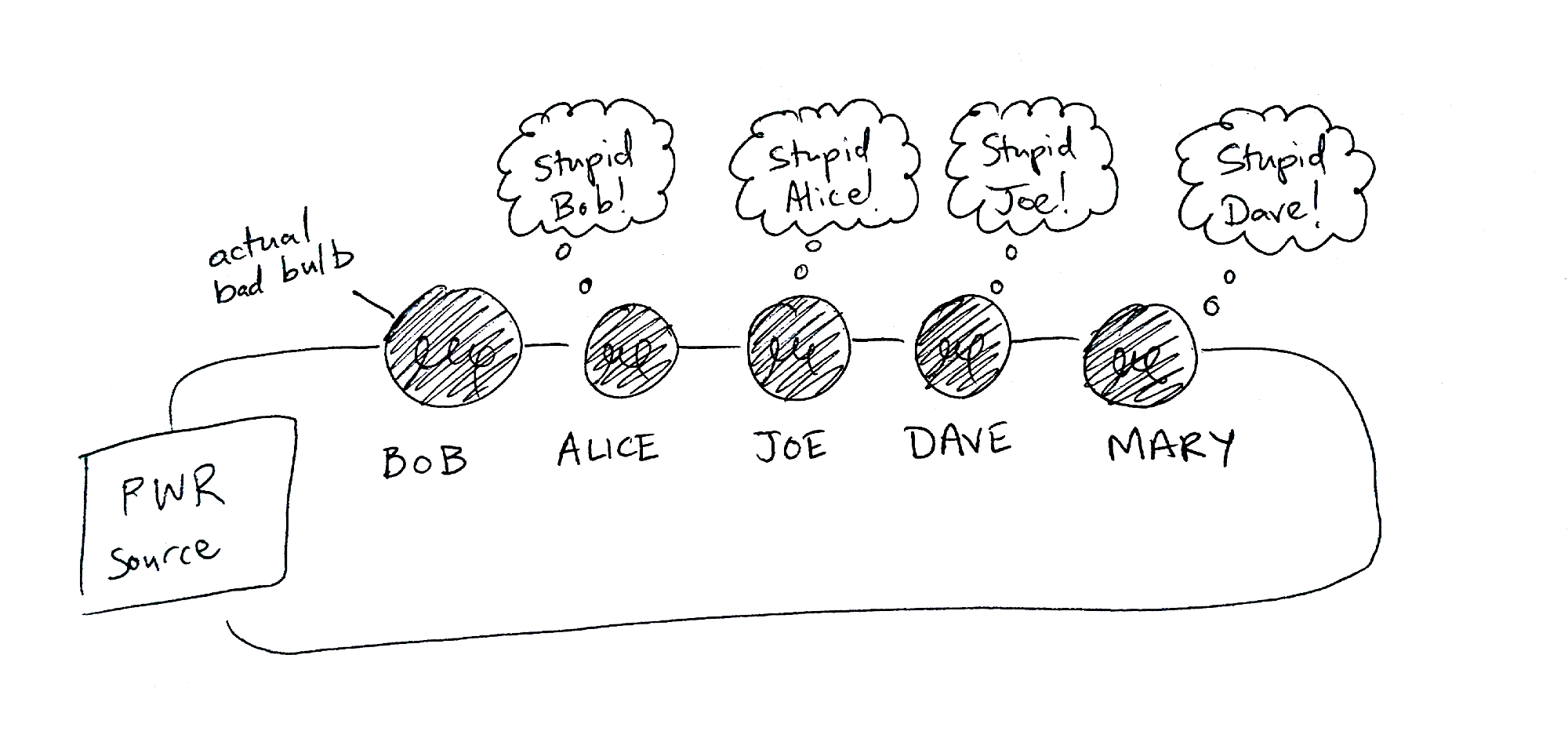

It can be difficult to identify the source of the problem in these situations. In a broken circuit, from a single bulb's perspective, the problem is that it's getting no current from the bulb before it. So it's that bulb's fault. But that bulb may not be getting any current from the previous bulb. From each bulb's perspective, it's the bulb one step earlier in the circuit that's to blame.

In the same way, we often can't easily tell the difference between someone who won't do their job and someone who can't. The outcome is the same either way. Both just look like bulbs that produce no light.

So organizations suffer from the same problems as series circuits. What can we do about this?

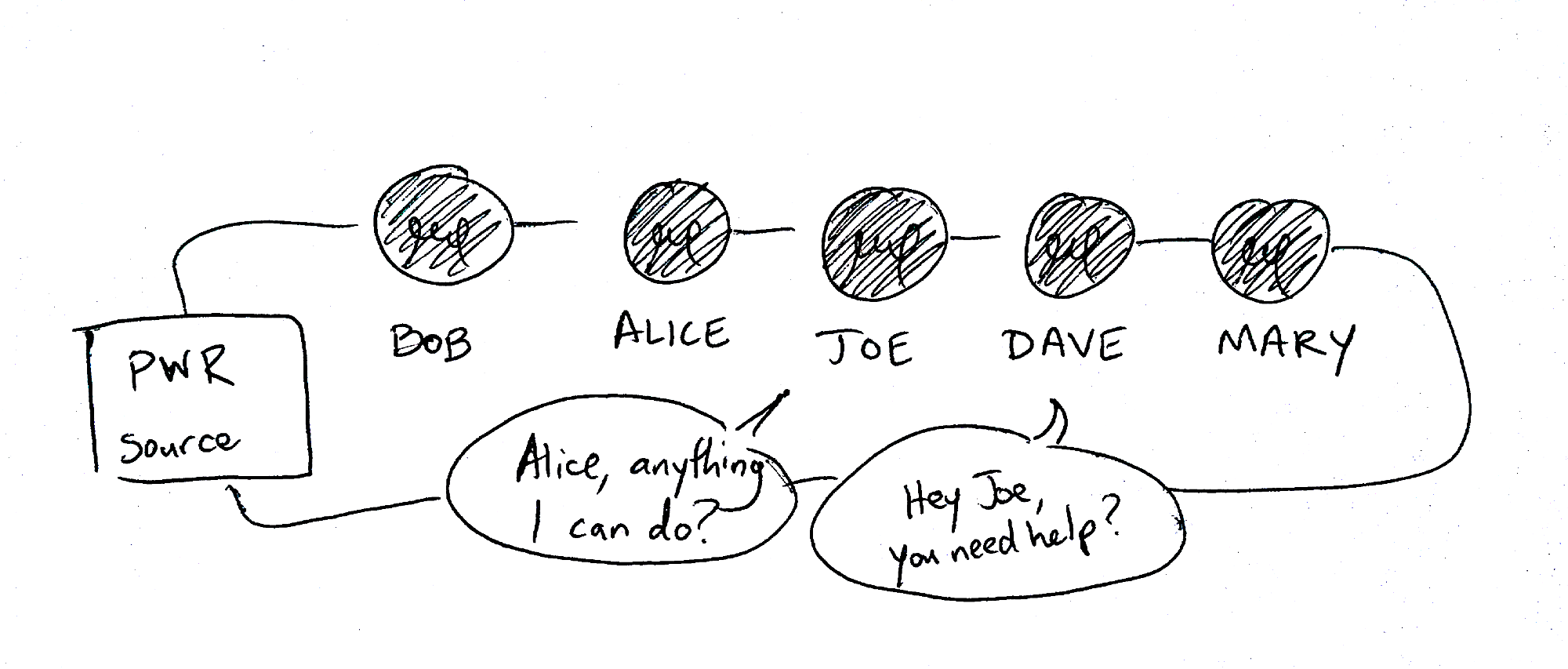

Imagine a new kind of light bulb that could reach out to nearby bulbs and repair them. The result would be a circuit that's resilient in the face of failing bulbs, a self-healing chain.

Our organizations could be like this if, instead of saying "That's not my job" when things go wrong, we reached out to assist those whose work we depend on. The potential difference this makes is huge. It's the difference between a string of lights that's completely dead and one where every bulb is lit.

Yes, it's risky. We worry that by going outside the parameters of our own jobs, we'll end up doing someone else's job for them, setting a bad precedent. In the worst case, it could become expected: we've created work for ourselves.

But consider the alternative. A world where every smart, capable person refuses to do work that's not strictly part of their job description is a world where a lot of smart, capable people aren't getting anything done.

For many of us, "That's not my job" is another way of saying, "It's not my fault." And that may be true. But I think it would be healthy for us to reverse our perspective on the issue: it may not be my fault, but does it affect me, and is it something I'm in any position to help fix?

This is the difference between a struggling project where everyone's trying to avoid being blamed for its failure, and one where everyone's actively trying to solve the problem. Which do you think has a greater chance of success?

When we stop saying "That's not my job" and start focusing on how we can fix the problems our projects face—and stop caring about whose fault they are, or who "should" be fixing them—our teams become self-healing chains.

-

I'm young enough that I don't remember ever having to deal with the horrors of series circuits myself! ↩