July 18, 2019

Here's a little tip I received fairly early in my career. I've heard this in various forms from various people, but the following is a quote from a boss I had not too many years ago:

Operate as if you already have the job that you want and then you'll be promoted and everyone will be surprised, thinking you had been in that role all along.

Good advice, bad guideline

For anyone who wants to be promoted, this is great advice. Getting a promotion is ultimately a matter of convincing someone—sometimes it's your manager, sometimes it's a committee—that you'll be effective in a new role. And the easiest way to convince someone of something is always to do all of the work for them. Put another way, the advice says: Make the decision easy for your manager by making it for them. Go ahead and do the job you want, and then they won't feel they're taking a risk on you.

I recently wrote about advice vs. guidelines because I wanted to write about this topic. While the above tip is great advice, it does not make for great guidelines. To understand why, let's take a brief detour to discuss the dual nature of promotions.

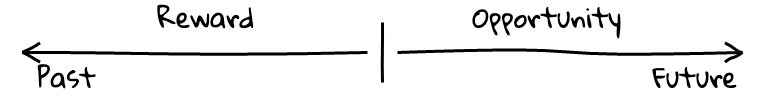

Reward vs. opportunity

A promotion is two things: a reward, and an opportunity. In my experience, every promotion decision involves both of these aspects to some degree; but one of them often dominates the conversation depending on the circumstances and the culture of the organization. My opinion is that at most companies, the promotion process over-emphasizes reward, which becomes increasingly problematic as employees get further along in their careers.

A reward is past-focused and is about the person. Employees are recognized for the work they've done, the value they've provided. When you give someone a promotion as a reward, you are saying, "This is for all of the great work you've done so far. You've earned it!" The emphasis is on you and what you've done.

An opportunity is future-focused and is about the role. Employees are given greater responsibility to take on a new role moving forward, generally to fill a business need. When you give someone a promotion as an opportunity, you are saying, "We need someone to do this, and we're counting on you to do it." The emphasis is on the role, and what you will be expected to do in it.

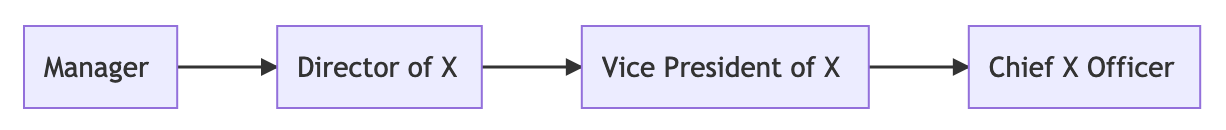

Reward-based promotions are generally not blocked by anything other than budgetary constraints. Take a group of individuals, put them all in the same entry-level role for several years, and most of them should have been promoted by the end of that period simply for having done good work. Most career tracks at most companies have some tiered structure allowing for individuals to be promoted in this way at least once or twice. This might look something like:

Looking at the tiered structure above, my observation is that promotions tend to be more like rewards on the left (e.g. being promoted from Junior Developer to Developer) and more genuine opportunities on the right (e.g. a promotion from Lead Developer to Principal Developer), because there are fewer openings for the positions on the right based on business need.

Opportunity-based promotions are therefore more of a bottleneck. You cannot simply give everyone in a group the same opportunity in a new role because there may not be a business need for that many individuals in the role. As an easy example: if everyone in the group wants to become a manager, it does not make sense to promote them all as then there will be no team to manage! In general, most management tracks have this issue as the nature of management is that there are fewer roles available the higher up you go.

The troubling distance between promotions and hiring

Now again consider the idea that you should do the job you want in order to be promoted. Again, my position is that this is great advice for an individual, but a bad guideline for an entire organization. The distinction between reward vs. opportunity helps to illuminate why.

This guideline focuses on the past. In that way, it instructs organizations to treat all promotions as if they are rewards. This becomes increasingly inappropriate the higher up you go in level. The positions with the most responsibility are not rewards; they are opportunities to have a bigger impact.

Meanwhile, when you look to hire someone into a role, their past is essentially unavailable. You do not reward a new hire for the great work they've done for your organization, because they haven't done any. Hiring by necessity must therefore focus on the future and the value that you expect a candidate will provide in the role. Hiring is always about filling a business need; it is always about providing an opportunity.

Now imagine that a fairly senior role has opened up in your department and someone needs to fill it. Two candidates emerge: an existing employee and an external candidate. When your organization's policy is defined as the guideline above, these individuals are faced with dramatically different requirements. The internal candidate must have already demonstrably operated in the role—potentially for an extended period of time (12 months or more is not uncommon)—while the external candidate simply has to convince their interviewers and the hiring manager they can do the job. The internal candidate is judged by their past; the external candidate is judged by their perceived future.

When you've worked hard for years to prove yourself and get a promotion, only to see someone else hired into the same role without having to jump through any hoops, it can stir up resentment.

A potentially even bigger problem is the paradigm this creates (really I should say, the paradigm it has created in the industry), where it is typically much easier to obtain a role that you want by going through another company's hiring process rather than your own company's promotion process. This is a recipe for losing your best senior people1.

How it needs to change

My conclusion is very easy to state but I realize that it's not so easy to put into practice. It starts with understanding the inherent asymmetry in a system where promotions are viewed as rewards, which are focused on the past, leaving hiring as the primary mechanism for filling roles based on business need, i.e. granting opportunities for the future. From there, the change I would like to see most organizations make is a shift towards providing more opportunity internally. Practically speaking what this means is more hiring at the bottom and promoting to the top.

For example, if your team needs a technical leader (maybe that's called a Principal Developer in your organization), rather than hiring a Principal Developer externally, consider promoting one of the more senior members on the team and hiring someone junior to backfill them.

One of the most obvious reasons we don't do this is that it feels like taking a big risk, giving someone an opportunity when they haven't irrefutably proven themselves. What if they aren't up to the task2?

The reality is that you're taking a big risk either way. Whether you're looking at someone external or someone internal who hasn't already been doing the job for a year or more, you can't know for sure how they'll perform in the role. At least the internal candidate has proven themselves capable in their current role; and they've contributed to your organization for this long and want a chance to do more, which is more than you can say (yet) for someone external.

As an organization evolves and grows, there will continue to be new roles that someone has to fill, creating opportunities. Choosing who receives these opportunities is ultimately about believing in people. And don't underestimate the amount of good you can do, for your employees and for the organization as a whole, by believing in the people you have.

-

The cynic in me recognizes that at some companies, this might actually be the evil master plan: out with the old, in with the new! ↩

-

Personally, I am a fan of explicit trial programs for things like this—Atlassian for example recently launched an apprentice manager program for employees who are interested in becoming managers—though that comes with risks as well. ↩