May 31, 2013

I recently started a JavaScript project called Lazy.js that's been getting quite a lot of attention1. Essentially the project is a utility library in a similar vein to Underscore or Lo-Dash, but with lazy evaluation (hence the name).

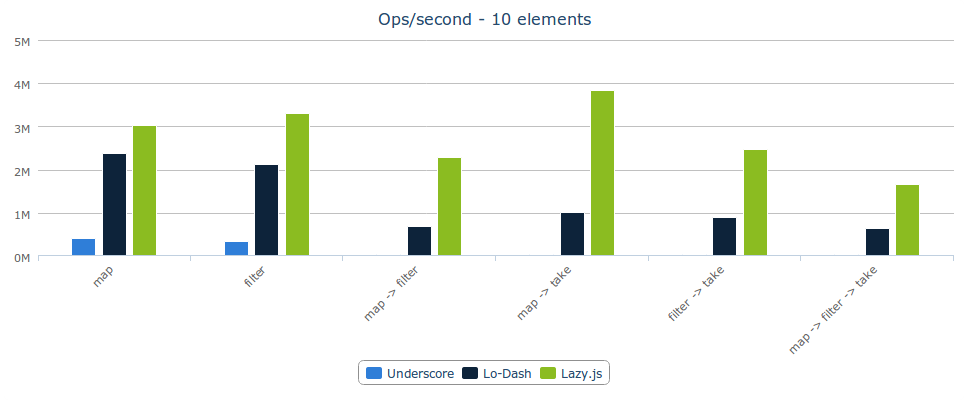

The reason I think the project has been piquing the interest of so many JavaScript developers is that it offers the promise of some truly solid performance, even compared to Lo-Dash (which is itself highly optimized in comparison to Underscore). This chart shows the performance of Lazy.js compared to both of those libraries for several common operations on arrays of 10 elements each on Chrome:

You can read more about what Lazy.js does on the project website or in the README on its GitHub page. In this blog post, I want to write a little bit about how it works, and what makes it different.

A different paradigm

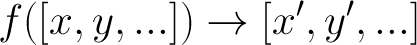

Fundamentally, Lazy.js represents a paradigm shift from the model of Underscore and Lo-Dash (starting now I'm just going to say "Underscore" for brevity), which provide a host of useful functions for what I'll call array transformation2: each function accepts an array as input, does something with it, and then gives back a new array:

This isn't how Lazy.js works. Instead, what is essentially happening at the core of Lazy.js is function composition: each function accepts a function as input, stores it, and gives back an object that can do the same. Then ultimately when each(fn) is called on the last object in the chain, it composes all of those functions together, effectively changing the behavior of fn.

Let's take map as an example. The idea of mapping is simple and something we do all the time; it basically means translating or converting.

Here's some code that uses map from Underscore:

var array1 = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

var array2 = _.map(array1, function(x) { return x + array1.length; });

In the above snippet, array1 is mapped to array2 using a function that shifts each value up by five. The process involves three significant parts:

- Look at every element in the array

- Apply the mapping function on it

- Store the result in a new array

This 3-step process is a core part of Underscore's paradigm: again, arrays go in, arrays come out. With Lazy.js, parts 1 and 3 above are not a core part of the paradigm. You can get the equivalent of step 1 with each, and you can get the equivalent of step 3 with toArray; but you're not required to do either of those things.

To illustrate what I mean, let's look at the map example again, this time using Lazy.js.

var array = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

var sequence = Lazy(array).map(function(x) { return x + array.length; });

Remember that sequence above is not an array; none of the elements of array has been accessed at this point. Which means we can do this:

// Result: 8

var middle = sequence.get(2);

...and dive straight into the middle of the sequence without iterating. This is what I meant by saying step 1 from Underscore's paradigm is not a core part of Lazy.js.

Similarly, we can do this:

/* Output:

* 6

* 7

* 8

* 9

* 10

*/

sequence.each(function(x) { console.log(x); });

...and, without creating any extra array, we've viewed the results. This is why I said Underscore's step 3 (storing results in a new array) is also not a core part of Lazy.js.

Digging a bit deeper

So I've said what makes Lazy.js different from Underscore, but I haven't really explained how it works in much depth.

I did mention function composition. Let's take a look at a concrete example to make that a bit clearer.

var array = Lazy.range(1, 1000).toArray();

console.log("First 10 squares that are evenly divisible by of 3:");

var sequence = Lazy(array)

.map(function(x) { return x * x; })

.filter(function(x) { return x % 3 === 0; })

.take(10)

.each(function(x) { console.log(x); });

Maybe that's a bit noisy—I just wanted to have a full example program—so I'll focus on just the map, filter, and take parts.

As I said earlier, each function in Lazy.js accepts another function and then creates an object to store it. So the result of map is an object—a MappedSequence--that stores its argument and exposes the same API as the object originally returned by Lazy(array).

MappedSequence(mapFn)

This object is then the "parent" of any objects it creates. The result of filter, then—a FilteredSequence--holds a reference to the mapped sequence as well as its filtering function:

MappedSequence(mapFn)

FilteredSequence(filterFn)

Next we have take, which creates a TakeSequence that stores the count we pass to it:

MappedSequence(mapFn)

FilteredSequence(filterFn)

TakeSequence(count)

Finally, when each is called, we compose everything together. In this example, the data underlying our nested sequences is an array; so each(fn) does just what you'd think: iterates over the source array, and...

- feeds each element to

mapFn, - feeds the result of

mapFnintofilterFn, - feeds those elements with truthy results from

filterFnto theTakeSequence, which... - feeds the first 10 results to

fn, then ends the iteration (by returningfalse)

Another way of looking at it is this. Let's forget about arrays (or collections, or sequences) entirely for a moment. The core idea behind map is, as I said, translation. This is independent of the idea of iteration. It's simply the idea of, for some value, mapping it to another value.

Same with filter: it doesn't necessarily have to do with iteration. The idea of filtering is, for some value, testing whether it satisfies some condition or not.

And so, if we don't think about arrays at all, we can still combine these concepts. For some value x, we can map it to y, and then we can filter that y to check whether it satisfies a condition.

// Looks like function composition to me!

filter(map(x))

As a pure replacement for Underscore—which it can be—Lazy.js is basically an inversion of the 3-step process I described. Instead of doing 1-2-3, 1-2-3, &c. for each operation, we can do 1 (for each element in the source...), then all 2s combined (every map, filter, etc. composed together), and finally 3 (store the results in a new array). You don't need to use Lazy.js that way—as I hopefully have emphasized quite enough by now!--but you can, if you're just looking for a drop-in Underscore replacement. And that wouldn't be a bad call, given the performance difference!

The reason I keep saying that isn't all that Lazy.js is about, though, is that there's a lot more you can do as a result of this different model. You can generate indefinite sequences, iterate asynchronously, map/reduce on DOM events (or any event type, really), lazily split strings, and more. Take a look at the Lazy.js website or—better yet—actually give Lazy.js a try and see for yourself what else you can do.

The road ahead

Thus far this project has received a much more enthusiastic response than I would've predicted, which is a bit daunting. That said, I'm not sure it's actually being used much out in the wild yet. I only just recently published it as a Node package; and while I've started working on documenting the code properly, I haven't quite settled on an approach yet. (In other words, the documentation is quite lacking at the moment.) Even the organization of the repository (names of folders, which files go where, etc.) is something I haven't really ironed out. So a lot is in flux.

That said, it would make me really happy if people start trying out Lazy.js for real and submitting issues to help me find bugs faster and prioritize working on the most useful real-world features.

I also attribute some of the library's sudden popularity to the project website, which includes a nice benchmark runner to compare Lazy.js against several other libraries and view the results in an intuitive and visually appealing format. In the back of my mind I'm planning to eventually refactor some code out of there and into another open source project specifically geared towards comparing the performance of competing libraries, or even standalone functions.

For now, though, I'll keep working on Lazy.js and hoping to get some feedback from users.

-

For me, anyway—as of the time I'm writing this, it has 865 stars on GitHub! ↩

-

I don't have a C.S. background, so I don't know if there's a academic term for these ideas. Probably is. ↩