April 17, 2013

I never actually worked in an environment like this, but I've read enough articles on The Daily WTF to have an image in my head of the old dusty, temperamental servers that companies used to have back in the 90s and early 2000s.

Those were dark days, from what I hear—when your business was victimized at the whim of an unpredictable piece of hardware. If the power went out, or the CPU overheated, or the hard drive failed, your site went down. It was as simple as that.

We live in a different era now, with PaaS and IaaS and all that cloudy good stuff. Your average tech-savvy business owner is going to know there's no particularly good reason to run your own server anymore if you're a small company. And if you're one of the large companies providing these services like Amazon or Google, you have been on top of the hardware problem for a long time, with data centers distributed around the country (or the world) connected in a controllable and reliable way. It's not an issue anymore.

This is a dream come true for everyone at the top of the food chain. The last thing you want in a high-up role is to be embarrassed by a problem at the bottom, far below eye level. The infrastructures that exist now for tech companies abstract servers into basically a sea of computing potential, which can be drawn from, predictably, as needed. (And on those rare occasions when outages do occur, it's still nothing to lose sleep over. It's Amazon's problem; they'll deal with it and apologize profusely in the morning.)

Dreaming of sliders

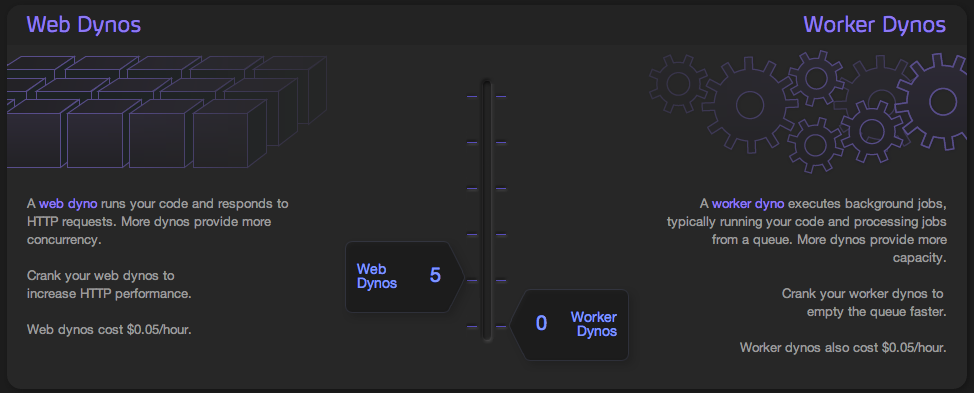

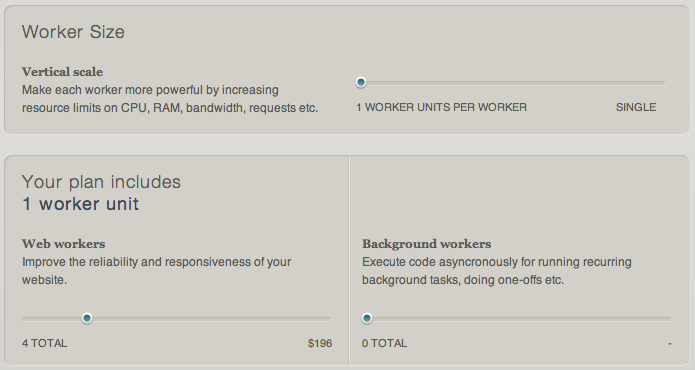

Essentially hardware is now a slider system, where increased scalability demands call for nudging a slider up, at which point additional hardware is automatically provisioned and dedicated to storing your data, hosting your applications, etc. This is evident on sites like Heroku and AppHarbor, which literally give you sliders to adjust how much computing power you want.

I think there's a similar dream a-brewin' in the industry when it comes to people. I also think it's wrong. But let me explain.

A couple of weeks ago, I read in the news that Apple was assigning some OS X engineers to work on iOS to help get the next version of the mobile operating system back on schedule (apparently it was falling behind). It reminded me of a famous essay by Fred Brooks called The Mythical Man Month, which is essentially a direct rebuttal of the notion that adding people to a software project speeds it up. Written in 1975 from experience at IBM, the essay provides a compelling argument that adding bodies to a delayed software project actually delays it further. This is now known as Brooks's Law:

Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.

It has amazed me, ever since reading Brooks's essay, how almost universally it seems companies ignore this principle1. They want so badly to be able to speed up software projects by adding engineers—to have greater control over their outcomes—that they'd rather believe Brooks's Law is wrong, or pretend to have never heard of it, than take it seriously.

Because that's the dream: companies want a slider system when it comes to people. Software project running behind schedule but you've got cash to spend? No problem! Just push the manpower slider up another 50% or so, and the project will zip right along up to your desired velocity.

A lot of what larger companies do is meant to facilitate this dream. They choose an approved set of tools and technologies. They prioritize extensive documentation on all of their projects and processes. They establish a clear and consistent onboarding process. The goal of all this being to establish a baseline that applies to every new employee, so that anyone who understands this baseline can be easily allocated to any project within the company with minimal ramp-up costs. (I'm reminded of tools like Chef and Puppet that serve a similar function for servers: establishing a baseline configuration so that machines can be seamlessly allocated to increase capacity.)

Remember that "sea of computing potential" I mentioned with hardware? This is what many companies want with people, too. It's why the terms "human resources" or "human capital" exist: the more human resources I stockpile, the more manpower I have to throw at any project that I want done quickly.

The problem with viewing people as resources

I recognize that to a certain extent, the strategies I just described make sense for large companies with hundreds or thousands of employees. If you know developers are going to come and go—and unless you're GitHub, you're kidding yourself to believe otherwise—you want to minimize the cost you pay each time that happens. It's also good to give people as much mobility between projects as possible, not just for the company's good but for theirs as well: no one wants to feel stuck on a project.

But I still think there's a pretty big problem with this people-as-resources fantasy. Whenever I hear startup founders lament being low on "engineering resources," I can't help but feel their perspective is tragically distorted.

Startups traditionally seek out the best and brightest developers they can snag, and they're often prepared to offer them substantial compensation (money, if they have funding, or equity) to do so. Most of the time, I believe this is wasteful. Why? Because of this people-as-resources notion, which is about abstracting engineers into a sea of engineering resources—so that when the business needs to scale, it can push up on the recruiting slider, get those engineers in the door, and really start cranking out product features (or whatever).

To be honest: I actually do buy into the whole 10x thing: that the best are 10x better than average2. Which implies it's worth paying a lot for the best people. So why is it a waste of money, again? Because for this abstraction to work—this idea that people are resources—individuals need to be equalized somehow, so that adding and subtracting them from the pool has predictable results. And equalization by definition requires dragging the top down while pulling the bottom up. When you hire based on 10x but then proceed to chase after the "resources" fantasy, you're basically throwing money away, buying at the top and then pulling down towards the middle.

An interesting comparison I'd make here is to how Google famously uses commodity hardware in their data centers. At one point in history this seemed counterintuitive to a lot of people; but I think by now enough other companies have scaled to the extent that many have learned the same lesson: in terms of cost per CPU power, you get a lot more bang for your buck—more value--by buying cheap servers and scaling horizontally. If you want to do the same with people, you need to Moneyball it: seek the most under-valued individuals you can find, knowing they aren't "star" players but confident that your equalization strategy will whip them into shape, netting your company another dyno to add to the manifold.

Which is it going to be?

I suspect there are many who would argue with me on this point, insisting that hiring the best people still delivers good value because, proportionally, if someone is 10x average but I'm only paying 2x average, I'm actually coming out ahead. Of course, this does make sense mathematically; but I think it's kind of missing the whole point of what I'm saying.

If your goal is to get a good value out of someone, that essentially means you're looking to under-compensate them somehow. I don't mean to suggest you should offer 10x the average salary for people who are really worth it. I just mean that this mentality by its very nature treats team-building as a zero-sum game, where the company benefits by paying its employees as little as possible—and there is no downside, because people are resources. This sets up the relationship from the very beginning in a bad direction. Either this person will become bitter about the arrangement and leave, or they'll simply become complacent and start performing way below their potential—at which point, there goes the value you were so excited about.

So I think you need to pick one: either view people as teammates that you're going to bring on for their creativity and their ideas and give as much freedom as you would want in their shoes; or view them as resources and give up on going for the "best" because you'll just end up overpaying.