December 12, 2018

When we use the word "software" we're really talking about two things. First there's the code, which is essentially a set of instructions, or routines. But just as an instruction manual doesn't magically accomplish a task, code by itself doesn't do anything. It needs to run in an environment: all of the requisite pieces, both hardware (e.g. a PC or server) and software (e.g. an operating system), that the code needs to work.

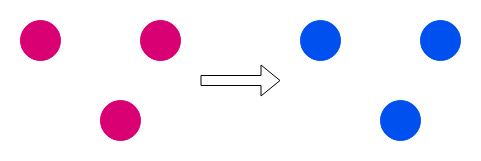

A deployment is when you take software that's running in a particular environment and you update its code.

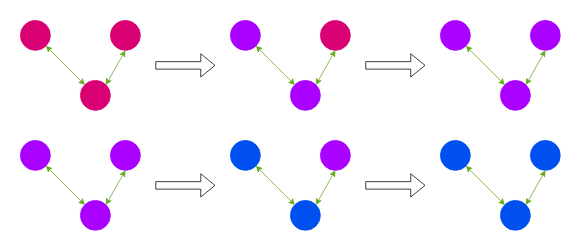

One type of deployment is called a rolling deployment, where you update slices of the environment (for example, groups of servers) in sequence, so that until the deployment is over you have both old and new code running at the same time.

Rolling deployments tend to be good for reliability. They require no downtime, since some of the environment is always running. They're also cheaper than some other deployment strategies, such as blue-green deployments, which require additional resources to run parallel environments.

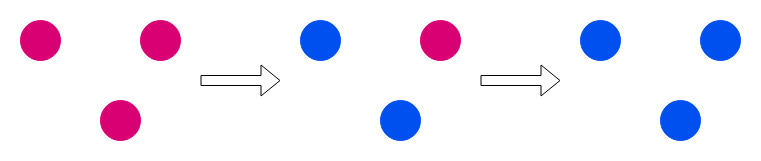

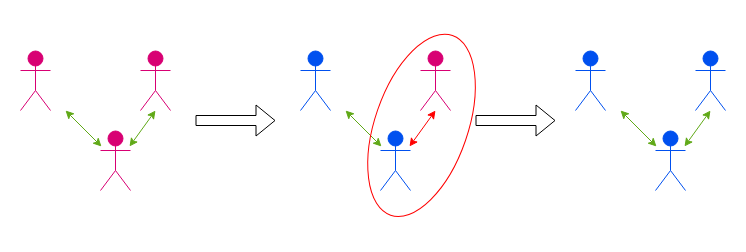

But rolling deployments also come with risks. Remember that code is a set of instructions. Sometimes one set of instructions contradicts another; in these cases we say that the new code is incompatible with the old code. For example, a field is removed from an API, but some of the old code was referencing that field. In a rolling deployment, this causes errors as the two incompatible versions of the code coexist for a time: one server expects the field to exist, but the server it interacts with fails to provide it.

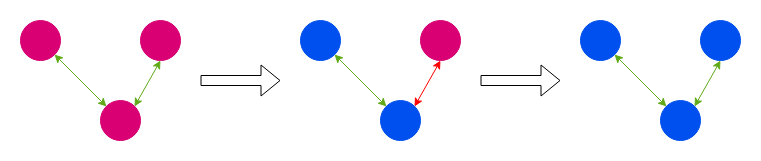

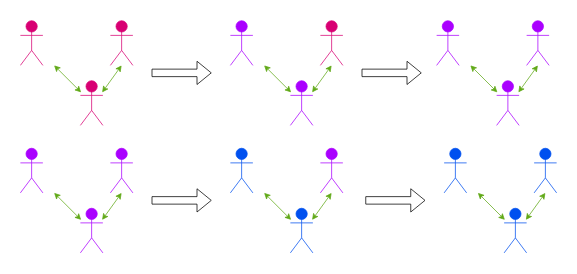

The "right" way to do a rolling deployment, therefore, is to do so in stages. To introduce backwards-incompatible changes (like removing a field from an API), you must first deploy a version of the code that doesn't use the field anymore. While this deployment is underway, servers running the new code are compatible with both the old and the new. In the next stage, after every server has this backwards- and forwards-compatible code, you can safely remove the field.

Culture is a bit like software. The traditions, values, and rules that we collectively share are akin to the code, and our society—i.e., every one of us, living together—is the environment in which it runs. Just as a set of instructions on its own does nothing, culture cannot exist without people to live it.

No two people have exactly the same version of the code since we don't all share exactly the same values or traditions. But the values we generally all do accept shift over time. For example, 150 years ago the people of the United States were divided on the issue of slavery; but today it is universally regarded as morally wrong.

In this sense culture is experiencing an ongoing rolling deployment, to one of the most complex environments imaginable. We're all running different versions of the code, and new versions of it are constantly being deployed, through art, pop culture, politics, the news media, schools, books, and a million other things. The code that says slavery is wrong is fully deployed at this point; but it took a while. Meanwhile, some new code is in the process of being deployed right now, and the deployment may continue through our lifetimes.

Sometimes our code is incompatible. Maybe you have a friend or relative who says things that are offensive to you, or who doesn't "get" a particular social movement that you believe in. At the same time, maybe you and I have some of our own outdated code running, and in a year (or two, or ten) we'll see things differently. In any case, when the old and new code coexist, it causes errors: misunderstanding, disagreement, conflict, and sometimes violence.

As with software, the way to prevent these errors is to make changes in stages. First you need to deploy a version of the new code that's still compatible with the old. In culture we call this tolerance. This means that rather than refusing to talk to your friend about politics, or disconnecting from them on social media, or generally allowing anger to dictate your interactions with those you disagree with, you engage with them. You understand that they are running a different version of the code. And until everyone's been updated to your version, you can't drop your support for other versions. (Besides, who knows? Maybe you're the one whose code needs updating.)

Earlier I used the word "right" to describe the multi-stage method for doing rolling deployments. In software, this is the way to do it if you want to avoid errors. However, there's a downside: it takes longer. Sometimes the old code is so harmful—for example, if it contains a critical security vulnerability—that the value of getting the new code deployed as fast as possible outweighs the cost of the errors.

The same can be said of culture, where sometimes an old tradition or set of values results in the oppression of those without power. Religious persecution, slavery, and the disenfranchisement of women are all examples of this. Throughout history there are examples where the deployments to correct these cultural problems have been violent, taking the form of riots, revolutions, and wars.

I'm not the one to say when a cultural change is sufficiently urgent that tolerance should be jettisoned and the stages skipped. I just know that if you want to deploy incompatible code without causing errors, you need to do so in stages. Likewise, those on the forefront of cultural change will need to adopt backwards-compatible code, and interact gracefully with those behind them, if we want to keep the peace.