January 15, 2011

For reasons not relevant to this blog, I have been thinking a lot lately about personal conflicts and how they evolve1. In particular, my mind has been concentrating a great deal on the scenario of conflicts escalating: for example, the phenomenon where two people are having a regular conversation, and this somehow leads to a disagreement, and eventually the situation develops into an all-out shouting match with both parties so angry with each other that it's often baffling to recall how the conversation began.

This can happen over a short or a long period of time. It can take place within a single ten-minute conversation; it can also span days, months, even years (in this case it might be the cause of a friendship's disintegration). It can also occur on a small or large scale. It might occur between friends, families, communities, even nations (throughout history, what war has not started as a smaller disagreement that eventually grew to something much larger?). I think we've all seen it happen, sadly, probably numerous times.

As I am a software developer, I often perceive parallels between real-world phenomena and software concepts. What I want to do right now is to discuss one such parallel: the similarity between escalating conflict (the real-world phenomenon) and mutual recursion (the software concept).

A note to those readers who aren't programmers: I will be including some source code in this post, but don't stop reading! I promise that this discussion is of a general nature and not strictly programming-related.

For those who can read it, consider the following code snippet:

void Provoke()

{

Console.WriteLine("Provoke!");

Respond();

}

void Respond()

{

Console.WriteLine("Respond!");

Provoke();

}

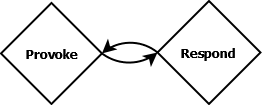

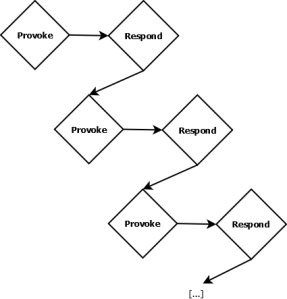

If I were to ask you, What does the above code do?, an initial response might be that it will print the words "Provoke!" and "Respond!" to the console over and over again, indefinitely. This might be one way to depict such a process:

This is how I believe we tend to visualize back-and-forth personal conflicts (if we are visual thinkers, anyway). We think of individuals locked in an ongoing dispute as somewhat akin to Dr. Seuss's The Zax, eternally stubborn, never budging. If two individuals are belligerent enough, and stubborn enough, they just might argue forever while the world around them moves on.

How many times have you thought this about two people arguing? This could go on forever, etc. But this is not an accurate view. As anyone who's witnessed or been a part of such a conflict knows, they don't go on forever. Nor does the code above. Developers with a keen eye will realize that my Provoke/Respond code snippet exhibits mutual recursion; it will not execute forever but will instead overflow the call stack.

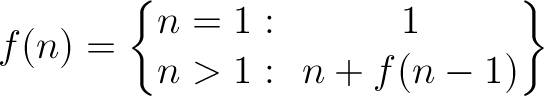

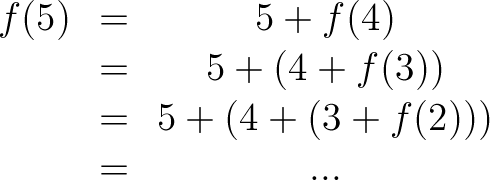

For the not-so-programmatically-inclined, a bit of explanation: recursion is like the Ouroboros, a dragon (or snake) devouring itself tail-first. A simple example of a recursive mathematical formula might look like this (forgive me if this notation is a little off; it's been a while since I've done any real math!):

Even if that looks like gibberish to you (not to insult anyone's intelligence—I just don't want to assume anything about my potential readers), notice one important detail: the function f(n) appears to be defined in terms of itself. (Contemplating the above formula for a moment, you may realize that it defines one way of calculating the sum of positive integers from 1 to n. Suppose n is 5, for example. One way to compute the sum of the numbers 1–5 would be to take the sum of the numbers 1–4 and add 5, right? Likewise, to get the sum of the numbers 1–4 you could take the sum of the numbers 1–3 and add 4. Continue following this process all the way down to 1, and you finally reach a stopping point: the sum of the numbers 1–1 is simply 1.)

So you can see why I compared recursion to Ouroboros. In order to progress along its computational path, a recursive function dives further "into itself" before arriving at a result. But there is another way in which recursion and Ouroboros are similar: like the formula above, the dragon must stop at some point.

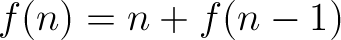

To illustrate this fact, consider the following "simplified" version of the above formula, in which I have eliminated the n = 1 branch:

At first, this formula appears to behave no differently from the first one. If n = 5, then we have:

But wait... when does that formula end? It doesn't. It goes to f(1), then to f(0), then to f(-1), on and on, infinitely.

Aside from the seemingly paradoxical nature of such a formula, it doesn't actually pose any threat to us. It is a rather meaningless oddity, nothing more. But in the world of software, where said formula might be translated into a computer program, this unending recursion suddenly represents a big problem, just as it would for the Ouroboros dragon, if it were a real creature.

While the dragon may think it can go on consuming itself forever, clearly it will not survive this process. Sooner or later, the constraints of reality will set in. The same danger exists for any recursive (or mutually recursive) function: it cannot be allowed to continue indefinitely as each call requires the executing environment to maintain an additional level of "depth." In order to make this clearer, I will borrow an idea utilized by Douglas Hofstadter in his excellent book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid and tell you a story (well, a few, actually):

A boy sat on his grandfather's lap and said, "Grandpa, tell me a story." The grandfather responded, "All right, grandson," and began to tell a story that his father had told him as a boy:

A boy sat on his father's lap and said, "Father, tell me a story." The father responded, "All right, son," and began to tell a story of when he was a boy:

A boy sat alone in the forest with a box of matches. He lit them, one by one, until he accidentally started a fire and burned the entire forest down.

"And that's why you don't play with matches," the father said.

"And that's why you don't play with matches," said the grandfather.

I know, I know—awesome story, right? What I was trying to illustrate was this: in following the above story, possibly without realizing it, you maintained a mental stack of stories, three layers deep. On the first layer, there was the boy on his grandfather's lap. On top of that layer, there was the grandfather's story of himself on his father's lap. And atop that layer, there was the story of the boy who played with matches. As the story concluded, you were able to "unwind" this stack of stories; when the innermost story of the boy in the forest concluded, you found yourself back in the story with the boy on his father's lap. And when that story concluded, you were able to return your attention to the first story of the boy on his grandfather's lap.

I promise I am going somewhere with this; bear with me just a bit longer. Below is a story that is at once similar to the previous story, yet at the same time very different (and very weird):

A boy opened a storybook and started to read. In the book was written:

A boy opened a storybook and started to read. In the book was written:

A boy opened a storybook and started to read. In the book was written:

[...]

Whoa there, let's stop that before it gets out of hand. The above story (in case you didn't catch this) is about a boy who reads a story about himself reading the very story he's in. In this way it is remarkably similar to the recursive formula described above: it never ends. What are the implications of this with respect to your ability to follow the story? Is it possible?

Remember the "stack" I talked about. If you could hypothetically follow a story such as the one above, this would mean you could continue adding layer upon layer to your mental stack indefinitely. Obviously, this is not possible, unless you have an infinitely large brain. In the same way, as computers do not have infinite resources, executing a program consisting of a recursive function which never terminates is not possible. It causes what is called a stack overflow. (Starting to make sense?)

Now at last let's return to the subject of conflicts. When two people argue, it is not like the simplistic "loop" diagram above illustrating a neverending back-and-forth between Provoke and Respond. It is more like the stories above, where each exchange—each layer--takes the conflict deeper, brings both parties further into an ever-growing stack of insults and bitter words. I believe that a more accurate visualization of personal conflict, then, would look like this:

The above diagram could go on forever, except that we don't have an infinite space to put it in; therefore, just like a recursive function, it has to stop somewhere. In software this stopping point is part of the design of any properly-implemented recursive function; it's called a terminating condition (like the n = 1 branch of the first recursive formula above). The terminating condition should be specified by the developer to ensure that his or her recursive function has a defined end; otherwise, the environment has to enforce its own terminating condition (by throwing a stack overflow error, for example) to avoid the undesirable outcome of simply crashing.

Or, of course, the environment does not enforce any such rule, in which case the process (and the computer along with it) does crash. When the process is a personal conflict and the environment is the real world, the consequences of this can be severe: one person storms out (of the house, the relationship, the family), physical violence erupts, a missile is launched, etc. These are the catastrophic results of an unchecked human conflict, just as "crashing" is the result of an unchecked recursive function in software.

So how does one prevent this from happening? We already know the answer for a computer program: by introducing a terminating condition. In the Provoke/Respond example, that terminating condition might be added like this:

void Provoke(int energyLeft)

{

if (energyLeft < 1)

{

Console.WriteLine("You win...");

return;

}

Console.WriteLine("Provoke!");

Respond(energyLeft - 1);

}

void Respond(int energyLeft)

{

if (energyLeft < 1)

{

Console.WriteLine("You win...");

return;

}

Console.WriteLine("Respond!");

Provoke(energyLeft - 1);

}

The above code represents a trivial solution to a nonexistent problem. Its purpose is merely to illustrate how the introduction of a terminating condition can turn a program that would otherwise crash into one that is perfectly harmless.

What's frustrating for me is when I see two people engaged in an argument where each one believes that he or she is being the "bigger person" and that it is the other one who's responsible for the conflict. Snide remarks, passive-aggressive comments, a superior attitude: all of these escalate an argument just as much as shouted insults and pointed fingers. In other words, it isn't whether you're shouting or not; it's whether you're adding more layers to the "stack" that affects the outcome of a conflict. Unless at least one person (preferably both) takes responsibility for establishing a terminating condition, the fight will continue to blaze—and the stack will continue to grow—until something or someone explodes.

In any case, I think our resemblance to computers in this respect really is quite striking. Like computers, we are susceptible to our own kinds of "overflows" (e.g., of emotion) when engaged in mutually recursive behavior (e.g., arguments). And unless one actively provides a terminating condition in such circumstances (apology? forgiveness?), a conflict can grow quickly beyond one's ability to control it.

But maybe I'm seeing more parallels than are actually there.

Anyway, this is one of my resolutions for 2011: to recognize when I am involved in a conflict of this nature, and to be the terminating condition. Maybe if everyone thought of it this way, our conflicts wouldn't last nearly as long as they do.

Incidentally, I think that in this respect, doing the "right thing" in one's life is actually quite a bit like designing software properly.

-

Clarification: this is no reflection on my marriage or any other aspect of my personal life. What I have been witnessing are a number of conflicts among others around me; and I have found these troubling. ↩