October 03, 2012

Recently my friend Chuck reminded me of a conversation he and I had ages ago about a company called Steorn. This is a company that publicly claimed, back in 2007, to have developed an overunity technology. Chuck chastised me for having persuaded him to take the company seriously; to this day, despite their refusal to back down, they have still not convincingly broken the second law of thermodynamics.

Most of my acquaintances with a modest amount of scientific knowledge, of course, dismissed Steorn from the very start. What the company claims to do violates a known law of physics, they argued; therefore it is impossible; therefore they are either lying or confused. Personally, I never did and probably never will fully sympathize with this attitude. While I agree that Steorn probably do not have what they have claimed (and I certainly have no intention of arguing with the laws of thermodynamics!), I disagree with the premise that we can be so sure of things like this that we are justified in rejecting them immediately.

This is actually the same topic I covered in my very first post on this blog. But it's something I feel quite strongly about, so I'll probably write about it again, and again, until I'm satisfied I've fully covered the topic in the way I want (i.e., never). This time around, I want to relate my skepticism1 in these sorts of matters to the concept of one-way-functions--a mathematical term that I'll define later in this post. But first, I'll start with a simple problem.

Recognizing patterns

Back in the old K–12 days, I remember sometimes taking tests with pattern recognition questions. As a kid, I was always frustrated by these questions because I felt that they generally had no right answer. For example, consider this sequence:

1, 2, 4, ...

What is the next element in the above sequence?

If you say 8, you're most likely thinking that the "pattern" illustrated above involves every value in the sequence doubling the previous value:

1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, ...

But there are other possible patterns. For example, we could start with 1, and then add linearly increasing values (+1, +2, +3, etc.):

1, 2, 4, 7, 11, 16, ...

Or the pattern could simply consist of the values 1, 2, 4 repeated over and over:

1, 2, 4, 1, 2, 4, ...

These are all patterns; and they all start the same way, which means that there is no "right" answer to a question like this. There is, in fact, an infinite number of possible patterns I could imagine that would begin with 1, 2, 4, and then proceed in an endless variety of ways. So there are infinitely many equally "right" answers to the question.

The problem of deduction

The human ability to recognize patterns and predict outcomes based on those patterns is deduction.

There is a game of deduction that a few of my friends like to play called Zendo.

In Zendo, one player—the Master—devises a rule involving the game pieces, which he then illustrates via two examples: one embodying the rule, and one not. These examples are designated true and false. The players then take turns assembling their own game pieces in different formations, asking the master whether or not their formations comply with the master's rule. Eventually, one or more of the players will deduce the rule by observing a pattern across the examples.

I was recently surprised2 when, during a game, after the master had given his initial two examples, one of my friends announced that he knew the rule already.

This declaration of having the answer so early in the game seemed absurd to me. And I think you can understand why, from my earlier thoughts on pattern recognition. There was no way my friend already knew the rule at this stage, given that there were many possible rules that would be consistent with the examples given.

Put another way: my friend had not narrowed down the possibilities enough to justify his feeling of certainty, at least to my thinking. He was guilty of overeager deduction.

That said, I can't really blame him. We humans do this all the time. We have to, because the alternative—i.e., basing our beliefs on logical certainties—is completely impractical. But I'll get to that. Time to shift gears.

One-way functions

In mathematics, a one-way function is one where computing the output for a given input is easy; but performing the reverse is much harder.

This is in contrast to a two-way function, which is easy to reverse. An example of a two-way function would be multiplication. Given an equation like y = 3x, when we apply the input of 5, we simply multiply 3 × 5 and get the output 15. Likewise, if we know the output is 15, we divide 15 &div 3 and conclude that the input must have been 5.

An example of a one-way function is prime factorization. Take some large non-prime number—say, 946,905,102,747. Can you tell me this number's prime factors, i.e., what prime numbers divide it evenly?

This is not an easy problem to solve efficiently. The only obvious way is to just go through prime numbers, one by one, until you've found all the factors. Finding an answer in this way would obviously take a very long time for a human being.

However, it is very easy to verify when I tell you that these are the factors:

27, 101, 419, 857, 967

Even without a calculator, it would not take too long to multiply these numbers together and confirm that they indeed all multiply up to 946,905,102,747.

Here, the function in question might be worded in plain English as: What do you get when you multiply all of these prime numbers together? It is very easy to compute the output of this function given the above factors as input. The reverse might be worded: What prime numbers would you have to multiply together to get this number? From the output, figuring out the input is much harder.

Data encryption

With one-way functions, then, what we effectively have are problems that are difficult to solve, yet whose solutions are easy to verify. It turns out that these are highly useful properties in the context of software security. One-way functions constitute one of the fundamental building blocks of data encryption.

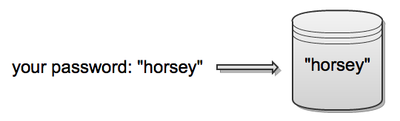

An illustration of this is the way passwords are stored. If you create an account with my website, and I then save your password directly in my database, then a hacker who breaks onto my servers can easily read your password.

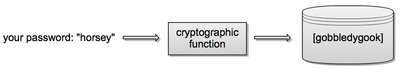

But suppose instead of storing your password itself, I store the output of some cryptographic (one-way) function, using your password (and perhaps a salt) as input.

Now, even if a hacker breaks into my system and sees your encrypted password, it will be very difficult for him or her to figure out what your password actually is--much in the same way it would be difficult for you to factor the number 946,905,102,747. However, it's very easy for my system to authenticate you when you enter your real password, just as it is easy for you to multiply the factors of that number together once I tell them to you.

One-way functions and black boxes

It might seem that I've veered off topic a bit. How are pattern recognition, Zendo, and one-way functions all related?

I believe the concept of a one-way function is broader than you might think from my initial examples.

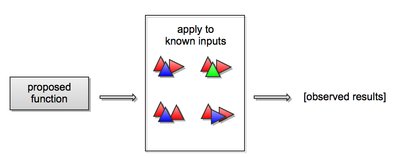

In Zendo, we can think of a rule as its own kind of function. The input to this function is a formation of game pieces, and the ouput is either true or false.

Clearly, this function is itself one-way. Given either true or false--even if you already knew the rule—how could you possibly deduce which formation led to that result?

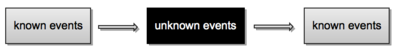

Of course, that isn't quite the challenge of the game. In Zendo, the players don't even know what the function is. This is why in the diagram above I've depicted the rule as a black box.

One way3 of thinking about black boxes is that they are a de facto special case of one-way functions: by convention, they only compute results in one direction; and since their internals are unknown, reversing this process—i.e., working out what the input must have been for a given output--is, in the best case scenario, really a challenge of deducing the inner workings of the box.

I think you can also think of a black box as a kind of "shifted" one-way function. Consider my earlier multiplication example: if we have a function y = 3x, then the forward case (multiplication) takes a value for x as input and produces a value for y, while the reverse case (division) takes a value for y as "output" and deduces a value for x. What is fixed in this example is the function itself.

Remember that in the case of a black box, we don't know what the function is. What we do know is what both the inputs and the outputs are given our firsthand experience. So we could reframe our puzzle-solving problem as a one-way function where the "input" is actually itself a function (or "rule", or "law"), and the "output" is a set of known results from applying this function to a known set of inputs. In this case, it is the inputs and outputs--our observations—that are fixed.

And we're now back to pattern recognition. What I've just described is a shifted one-way function in the same way that Zendo is: the inputs are fixed, and outputs may be observed, but the function itself is unknown. Furthermore, while it is easy to "verify" that a theoretical function does indeed produce the observed outputs for the known, fixed set of inputs, going the other way is near impossible—in the same way that there is no right answer to a pattern recognition problem.

The Sherlock tendency, or: humans and overeager deduction

Have you ever noticed that in detective stories, when the brilliant detective protagonist finally cracks the case, he generally reveals the full narrative of what happened to a room full of mesmerized listeners? In this narrative, he paints a vivid picture of how the villain prepared, all of the meticulous steps he took to avoid detection, and all of the little mistakes he made leaving clues that ultimately led the detective to expose him.

Here's why these stories, though I generally quite like them as entertainment, nonetheless fall short for me in terms of logical satisfaction. They are illustrations of what I will call the "Sherlock tendency", which is this: as human beings, once we have identified a plausible explanation for some event, we think we have uncovered the truth.

In the abstract, this is not any different from the "overeager deduction" I accused my friend of in Zendo. It is also the same as observing a sequence such as 1, 2, 4 and feeling certain at having recognized the underlying pattern.

This is all a plausible explanation really is—a proposal for a function which, when applied to the known, fixed inputs of a situation, is consistent with the observed outputs.

Let me try rewording that. Sometimes, we know certain things that happened at one time, and we also know things that happened at a later time; but we aren't sure what happened in between.

Any murder mystery is an example of this. The victim was alive at one point; later he was discovered dead. The mystery is what happened to him.

A plausible explanation is an attempt to solve the mystery by proposing what the unknown events above might have been while remaining consistent with the events that did happen. This is clearly not the same as a certainty. And yet I seem to observe it over and over again, in practically every aspect of the world we live in: history, economics, politics, etc. As long as we can construct a narrative which is consistent with the experiences of our lives and the information we believe we have about the past, we feel justified in subscribing to all that narrative implies.

It's an easy trap to fall into, because when an explanation is inconsistent with what we know, we can generally rule it out. I guess our natural instinct is to therefore run with consistency when we find it.

Why are we like this?

Not that it particularly matters, but I do have a hypothesis as to why we humans tend to think in this way.4

In the very beginning of my explanation of one-way functions, I mentioned that they are hard to solve in one direction. This is fundamentally where the term comes from. And so when we think of the mystery of life as a one-way function, where we know what we've experienced and we are compelled to make sense of it, we find ourselves in a predicament. It is very hard to solve this problem. In fact, it may be impossible. So our brains aren't up to the task.

And yet there is a tremendous advantage to understanding the world—both practically and emotionally. Practically speaking, we're better able to predict and manipulate our environment when we understand its rules—so a greater capacity for understanding is an advantage. I also think we're biologically hard-wired to feel rewarded or even euphoric whenever we're able to solve difficult mental problems, for just this reason. It's a kind of positive reinforcement, encouraging us to pursue even deeper understanding. (It's one of the reasons I believe humanity has advanced so far in science and technology.) And so emotionally, I think it makes sense for humans to crave this experience: of figuring things out, of "solving" the mysteries of this world and of our lives.

Heuristics in software

In computer science (and other fields as well) there are classes of very hard problems that cannot—at least not yet--be solved efficiently. One such class of problems is known as NP Complete. The NP stands for non-polynomial (time), which basically means that these problems take so long to solve, the time required—as a function of the size of the input—cannot even be expressed by a polynomial expression (e.g., t = n2).

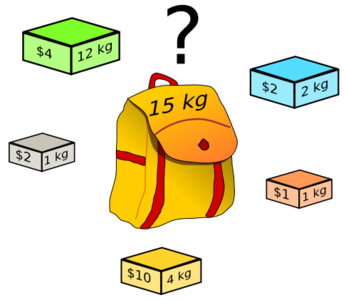

One of the easier-to-explain5 examples of an NP Complete problem is a famous one known as the Knapsack Problem, which is this: given some container of finite capacity and a set of items with differing weights (or sizes) and values, find the optimal assortment of items that can be stored in the container.

I happen to have a bit of firsthand experience with this problem, believe it or not, because at Cardpool I recently implemented a feature that allows customers to specify a total card value they'd like to purchase and then automatically populates their cart from available inventory6. This is essentially a special case of the knapsack problem where every item's "weight" happens to also be its value (in fact, internally we still refer to the feature as the "knapsack" feature).

Why do I bring this up? Well, in building this functionality, I was already aware that it's really an NP problem. Therefore I knew it wouldn't be realistic to try to solve with 100% accuracy or correctness; taking on a famously hard computer science problem for a simple convenience feature on a retail website would be a bit overkill. Instead, what we software developers do in situations like this is figure out heuristics, or rough solutions that are good enough for practical use.

That's what I did. I wrote a very basic algorithm—which is absolutely not a complete or strictly "correct" solution—and from my tests, sampling thousands of randomized carts, I found that it generally filled them to about 94% of the desired total value. My team and I agreed that this was good enough, and we moved on.

Heuristics in the brain

This is what we all do. This is how our brains work. In this world, full of so many competing ideas and possible explanations for the experiences we have, it is not feasible to comprehensively consider every possibility, with all of its nuances, any more than it is possible to efficiently solve an NP Complete problem. There are just too many ideas and not enough time.

So we exercise our internal heuristics, however we may have formed them over our lifetimes—forged by some mysterious blend of instinct, intuition, education, and so on—and we narrow down the options that our brains subconsciously deem worthy of consideration. The more we refine this ability, the more quickly we're able to arrive at a final decision; this in turn gives us the emotional reward we're after and propels us forward.

Some of us are able to do this quite quickly, which can be advantageous even when it doesn't lead to the truth, or to a "correct" result. We get away with it, I believe, because most of the time this strategy leads us to an understanding that is good enough--just like my knapsack algorithm was good enough, or like Newtownian physics was good enough until Einstein came along, or how if you pick any sufficiently controversial topic chances are you'll be able to find intelligent, well-reasoned arguments on either side--because the truth is complicated, and it's not possible for our brains to weigh every available piece of evidence and arrive at complete certainty with respect to such issues (that's why they're controversial). They are really tough one-way functions; the best debaters among us simply have the best heuristics, albeit ones that could well have led them in opposite directions.

Conclusion

I think it's important to realize that, at a very fundamental level, we actually know very little. The views we have adopted throughout our lives are informed by plenty of experience, sure; but there is so much universe out there, and our experience covers a relatively miniscule portion it. Our brains adapted to this early in our history, and as a species we developed a knack for using heuristics to form a good enough understanding of the world, so as not to end up paralyzed in deep contemplation our entire lives.

Of course I'm speculating a bit here! But can you blame me? I am after all saying that some form of speculation is all that any of us ever does.

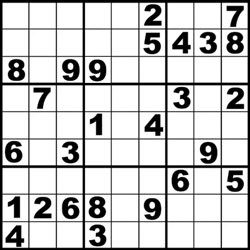

I'll leave you with one final analogy. Have you ever played Sudoku? It's a great game, though it can be rather maddening when it's too hard (my wife got me a book of Nasty Sudoku and it kills me). Have you ever had that sinking feeling when you're most of the way through a Sudoku puzzle and suddenly you realize you've hit a contradition—there must have been a mistake (probably on your part)?

This can be very easy to miss when it happens, especially if it occurs early in the puzzle. With so much unknown, a slip-up or illogical move may well not result in any obvious contradictions.

Now think of life as a Sudoku puzzle, but obviously much larger—with a grid extending as far as the eye can see in any direction: hundreds, thousands, millions of squares. You're never going to fill in the whole grid; that would be tantamount to fully understanding the entire universe. But you'll still make gradual progress, coming to understand more and more with age. However, you'll also make mistakes once in a while, even if you're good; and these mistakes will eventually lead to more mistakes, as happens in Sudoku. If you're honest with yourself, you'll therefore have to accept two things: that some of the grid you've already filled in is wrong (though you hope it's a small fraction), and thus if you ever compare your grid to someone else's and notice a discrepancy, you must be open to the possibility that theirs could be right.

And so the next time someone insists to me that Steorn cannot possibly have achieved overunity, or my friend claims to have immediately identified a rule in Zendo, or I see a detective movie with a resolution that neatly ties up all the details of the crime, I will remain skeptical. The universe is a one-way function; and while it may be easy for us to recognize when ideas are plausible, it is much, much harder to ever find the truth.

-

Ironically, with Steorn, I'd argue that disbelief is the default attitude and therefore those who dismiss the company outright are not really skeptics. Rather, those like myself who disagree (or at least did originally) that the company can be immediately dismissed are the skeptical ones—i.e., the ones skeptical of others' certainty. ↩

-

To be clear: my friend believed that he understood the master personally so well that he had a strong intuitive sense of the sort of rules he would think of. I remain skeptical. ↩

-

No pun intended—I swear! ↩

-

Notice that this hypothesis is itself a demonstration of the Sherlock tendency! Recursion, anyone? ↩

-

By which I mean, the only example I know of off the top of my head besides Traveling Salesman. ↩

-

If you'd like to see this feature in action, try using the "Bulk Purchase" button on Cardpool's Home Depot page and searching for, say, $2000 of cards. ↩