January 23, 2020

Many software teams use the term "spike" or "research spike" to refer to a particular type of task where the primary work involved is some sort of research or investigation.

You can find plenty of articles out there defining what a spike is and suggesting when it's useful. This post comes from my own experience and proposes a pretty simple definition that, at least for me, makes the value of a spike perfectly clear. It also helps to avoid a common pitfall I've seen some teams fall into (including some of my own!), saving time and improving outcomes.

Two axes of measurement

A task that might be assigned to a software developer (or practically any worker) involves two characteristics: the scope of its requirements, and an estimate of the work required.

The requirements for a task, also sometimes known as acceptance criteria, tell the developer what the desired outcome of the task is. Sometimes requirements can be fairly broad. This is why it helps to talk about scope, which clarifies the precise boundary of the requirements, i.e. what's in and what's out. Another way of phrasing this is that scope tells you the size of the output.

An example of this would be a task with the requirement of allowing users to change their contact info. Questions about scope might include: Which fields should be editable? Does this include an API? Does this include notifications?

Meanwhile, the estimate for a task represents how much work it's expected to take. Some teams measure this work in time, others measure it in "points"; but in either case the intent is to have an idea of just how big the task is, to help with planning and prioritization. Another way of phrasing this is that the estimate tells you the size of the input.

So these are our two axes by which to measure a task. Requirements are determined by scope, which tells us the size and shape of the outcome, i.e. the output of the task. The estimate tells us the size of the work necessary to complete the task, i.e. its input.

How a spike differs from a typical task

For every kind of task, the estimate can inform the scope to some degree. In the example above of allowing users to change their contact info, suppose that introducing an API for this feature significantly increases the estimate. The team might decide that this is therefore out of scope to allow the dev responsible for the task to complete the work sooner.

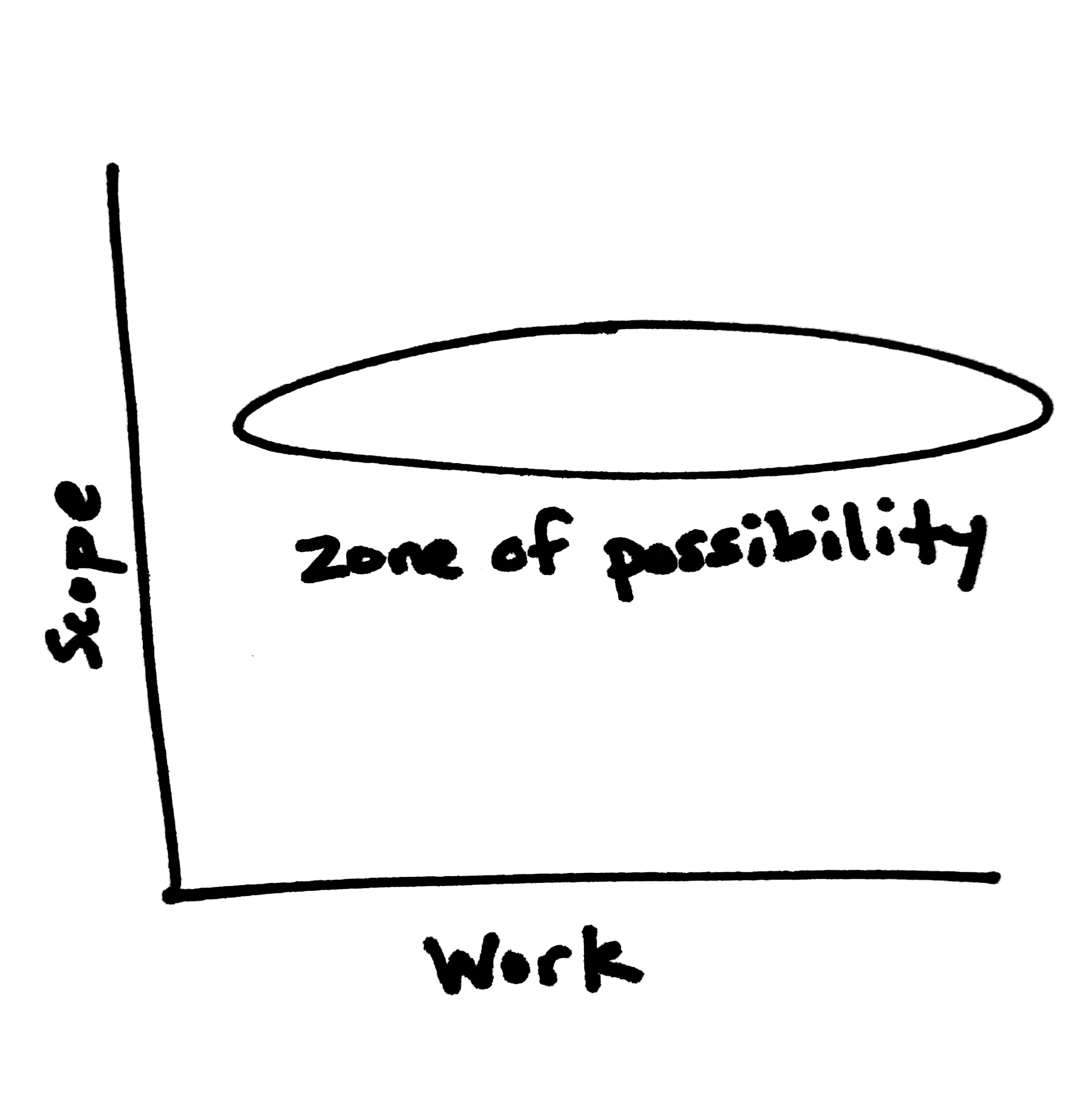

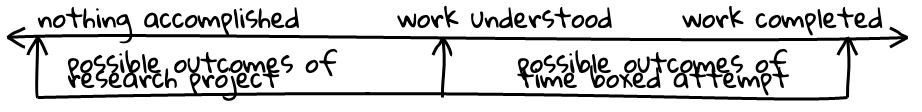

However, generally speaking, the scope of requirements for a task is fairly fixed while the amount of work invested is variable. Any negotiation around scope usually takes place before the work is started. Once the dev gets to work on the task, the team might expect it to take one week; but if it turns out that the estimate was wrong and the dev ends up needing another week, they'll take another week. The following image visualizes the resulting "zone of possibility" for a typical task, where the outcome is fairly well defined but the work is variable.

Earlier I mentioned a mistake that many teams make. This is to treat a spike as a research project where the outcome is defined as something research-y: maybe an article documenting the research, or a presentation to the team, or (at best) a backlog of tickets to actually do the work. Notice that this approach treats a spike the same as a typical task: the requirements (what the outcome should look like) are defined from the start, which leaves room for the work to be variable: if it takes a team member a day, a week, or a month to produce the paper/presentation/whatever, so be it.

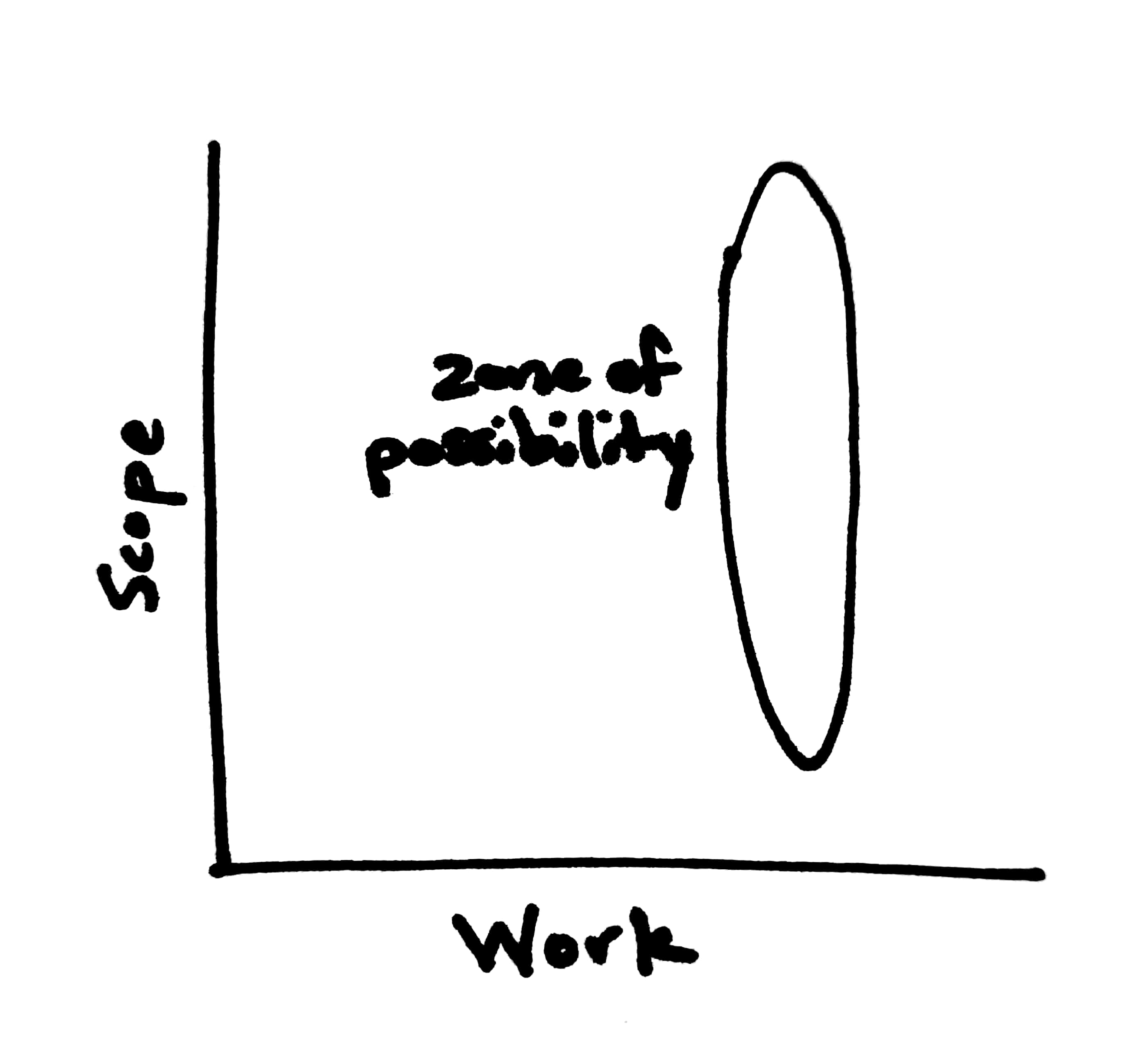

My proposed definition of a spike is nice and simple and I believe it leads to better results. A spike should not be viewed inherently as a research project, though research is undoubtedly part of it (as it can sometimes be for any task). Neither should the amount of work invested in a spike be allowed to be variable. Rather, a spike is the inverse of a typical task in that the work is fixed and it's the scope that is variable.

A spike is great for those situations when you have a finite amount of time, and there's something you'd like to get done, but you aren't sure whether it's feasible in the time you have. The only way to find out is to actually give it a try. If you are able to complete the work in the available time, great! If not, the spike is your best bet at establishing a trustworthy estimate for later. (My recommendation is to budget some time at the end of the spike to document the progress you made, how much work you expect is left, and what you learned.)

Probably the most crucial difference between what I'm describing and the "research project" approach I described is that, if a spike is inherently a research project, then the best-case scenario is that the work is merely more well-defined at the end of the spike. There is no chance that the work is actually completed! On the other hand, if a spike is a time-boxed attempt to do the work, then the work merely being well-defined is the worst-case scenario. The best-case scenario is that the work is done.

The best case scenario from one approach is the worst case scenario from the other approach! How can this be? It isn't like just thinking differently about a spike magically creates resources.

This is where it wouldn't be responsible for me to try and offer an explanation without the significant caveat that I am not a trained psychologist (or sociologist). But I do believe that the kinds of goals we set for ourselves can make a very real difference. It's where the saying "Shoot for the stars" comes from: the message is that the higher you aim, the higher you'll get. The unspoken corollary, of course, is that when you aim low, you can't expect to get very high.

A team will normally pursue a spike when something seems like a lot of work, perhaps bigger than they believe they can achieve in a reasonable amount of time (for some definition of "reasonable"). When the goal of the spike is simply to produce an estimate, or some tickets, that's aiming low. Really what I'm saying is that we should aim higher: take the thing that seems like it might be too hard, impose a time limit on yourself to cap the risk, and actually give it a try. Maybe it will turn out to be easier than you expected; or better yet, it is hard, but the work is energizing and the team rises to the challenge!

When the time runs out, if the work isn't done, at least we should have a good estimate of the work remaining, and probably some tickets. Which is the best we could have hoped for if we aimed low anyway.